Necropolis Records XII

2025-11-24

by Niklas Göransson

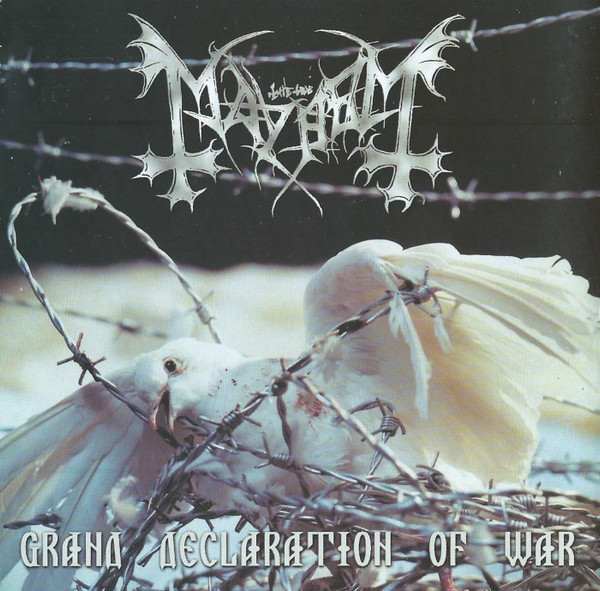

With Grand Declaration of War on the horizon, Necropolis stepped into pacts born of pressure and ambition. What followed was the beginning of a new order – one driven by alliances, leverage, and obligations impossible to outrun.

PAUL TYPHON: I flew to France with one goal in mind: securing the US license for MAYHEM’s “Grand Declaration of War”. By then, things had grown increasingly competitive, and domestic rivals like Century Black were also in the running. That pushed me even harder – it became a personal challenge.

Following Euronymous’ murder and the posthumous 1994 release of “De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas”, Hellhammer stood as the sole remaining member of MAYHEM. Over the next few years, he rebuilt the line-up – first bringing back Maniac and Necrobutcher, both of whom had appeared on the 1987 “Deathcrush” EP, then recruiting a young guitarist known as Blasphemer.

PAUL: I had mixed feelings about the band continuing without Euronymous, but Hellhammer and I always got along. He gave me an early preview of the new MAYHEM through “Pagan Fears” and even sent me a photo of the line-up before it was officially announced.

Aside from the “Pagan Fears” re-recording featured on “Nordic Metal: A Tribute to Euronymous”, the band remained silent until 1997, when Misanthropy Records issued “Wolf’s Lair Abyss”. The EP was followed by MAYHEM’s return to the stage and news of their upcoming second full-length.

PAUL: Hearing new MAYHEM material was both painful and liberating. Painful because Euronymous wasn’t there, and he probably wouldn’t have released something like that; liberating because Hellhammer, Necrobutcher, and Maniac were, and no one had the right to stand in the way of their art.

Despite several larger labels circling MAYHEM’s comeback, Season of Mist founder Michael Berberian won them over through sheer audacity. A friend visiting Oslo put Necrobutcher on the phone; seizing the moment, Berberian launched into such an impassioned pitch that the bassist flew to Marseille shortly after.

Knowing Season of Mist were up against competitors drawing from far deeper pockets, Berberian took an enormous gamble by offering the band an advance he didn’t yet have. Once the contract was signed, he sold nearly everything he owned, moved back in with his parents, and raised the promised funds through risky wholesale deals – effectively betting the label’s entire future on MAYHEM.

PAUL: Michael and I had spoken beforehand and built a solid relationship, but he wanted to meet in person. I thought, ‘Releasing the new MAYHEM five years after “Nordic Metal…” would be such a full-circle moment’, so I made sure to go over there and secure the license.

Paul met Michael Berberian at MIDEM in Cannes, France – an annual marketplace where publishers, distributors, and artists gather to network, negotiate, and sign deals. The 2000 edition took place in late January, while the new MAYHEM album was still a work in progress.

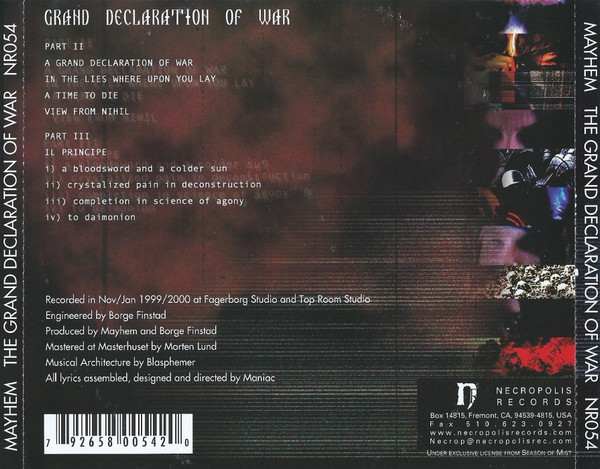

PAUL: At that point, my focus wasn’t so much on hearing the album as on what it could do for the business. Michael had some interesting terms; firstly, he wanted to print the booklets himself and then ship them to our manufacturing plant in the US so they could be inserted there.

What would be the point of that?

PAUL: That way, he’d know exactly how many discs we produced – pretty clever on his part. I agreed, and this became a whole story in itself. Secondly, any US label taking the MAYHEM release also had to put out NOCTURNUS’ comeback album, which I really didn’t want to do.

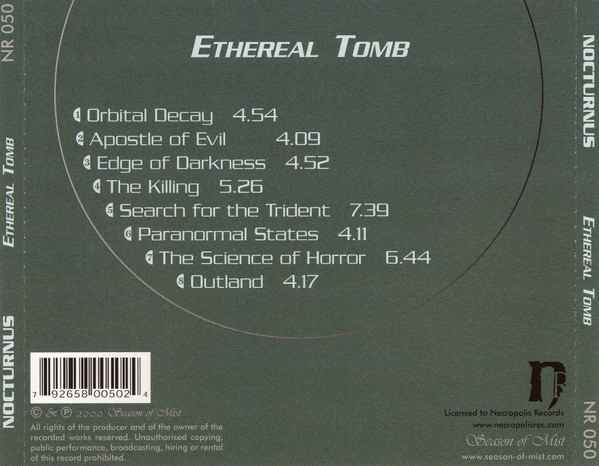

In 1999, Michael Berberian began a concerted effort to elevate Season of Mist from the underground. Signing the newly reformed NOCTURNUS was intended to strengthen the label’s standing among more established European imprints.

PAUL: I love NOCTURNUS with Mike Browning – and “Abominations of Desolation” (MORBID ANGEL) too. His vocals on those records are incredible; that’s how death metal should sound, same as the INCUBUS demo. I’ve always had huge respect for him, so knowing he wasn’t in the band anymore was a big letdown.

After INCUBUS capsized, Mike Browning formed NOCTURNUS as drummer–vocalist. In 1990, following two demos with a revolving line-up, they recorded their groundbreaking debut, “The Key” – the first death metal album to incorporate keyboards.

Shortly after the 1992 follow-up, “Thresholds”, internal tensions, Earache’s insistence on adding a dedicated frontman, and disagreements over lyrical direction culminated in NOCTURNUS firing its founder. Two of the members Browning had brought in then secured the rights to his band name.

This post-Browning faction survived only six months, but that didn’t stop them from using the trademark to block a later NOCTURNUS reunion by the original members. Then, in 1999, the mutineers re-emerged with “Ethereal Tomb” – the album effectively forced upon Necropolis.

PAUL: The NOCTURNUS condition was the only downside – I hated it. Still, winning the rights to license “Grand Declaration of War” felt huge. I knew we had all the right pieces in place, and everyone at the label fully believed in the project.

PAUL: It’s funny, because I used to hate it when METALLICA said, ‘We can’t keep making “Ride the Lightning” over and over.’ I’d think, ‘Rubbish – that’s exactly what I want you to do!’ But with a bit of distance and maturity, I’ve come to see their point. The right thing, creatively, is often to catch people completely off guard.

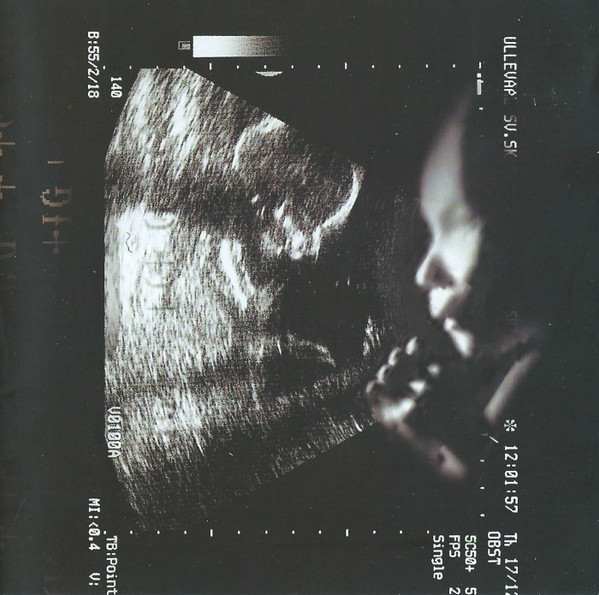

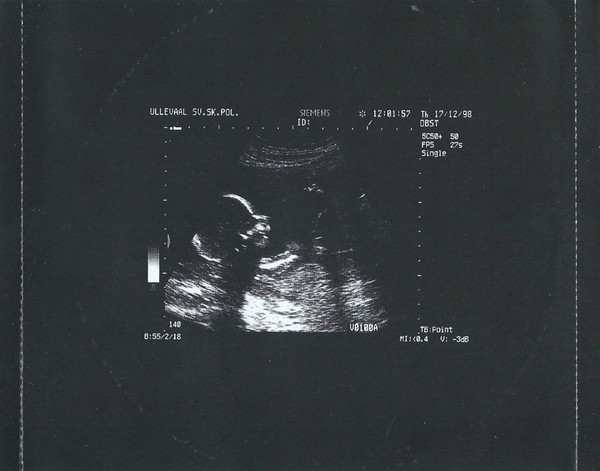

Where MAYHEM’s “De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas” had set the orthodox template for Norwegian black metal – cold repetition, an ecclesiastical atmosphere, and Euronymous’ mesmerising tremolo work – “Grand Declaration of War” veered off in the opposite direction.

Blasphemer’s riffing was technical, jagged, and militaristic; the production clean, clinical, and heavily triggered; and the songwriting fractured into movements rather than songs. Electronic percussion, noise-industrial passages, and long stretches of spoken-word narration replaced the cathedral-like ambience of its predecessor.

PAUL: What really stood out to me was how much courage it must’ve taken to make such a bold and unexpected move. Whenever a band does that, I think they’re doing something right – strange as it may sound. Playing it safe and repeating yourself is to take the easy route.

Would commercial failure have meant serious – or even fatal – trouble for Necropolis?

PAUL: Not really. We gave them a $10,000 advance, which worked out to roughly a dollar per record. Plus, we had to press the album, handle promotion, and commit to a lot of other promises – but that still wouldn’t have put Necropolis under. By then, fear of failure didn’t exist; it was more like, ‘This has to work.’

Leading up to the millennium shift, Necropolis hired New York-based publicist Jon Paris to expand its media outreach. The label also entered an agreement with Big Daddy Distribution in New Jersey.

PAUL: Bringing in Jon Paris, who’d done PR for Earache and MORBID ANGEL, gave me confidence. Big Daddy wasn’t my preferred option – but they promised to get our records into every store, which was my goal. With a major release like MAYHEM coming up, we had no choice.

Was this similar to Full Moon’s arrangement with Dutch East India?

PAUL: Yeah, a lot of labels had those kinds of setups. The big one back then was Relativity Entertainment Distribution, who worked with Relapse. I kept trying to get in – but in lieu of that, Big Daddy offered something similar. I remember attending one of their little get-togethers in New Jersey, where I met Martti from Olympic.

At the time, Illinois-based label Olympic Recordings worked with bands like GORGUTS, SOLITUDE AETERNUS, MONSTROSITY, and ANGELCORPSE.

PAUL: I also recall a goth imprint, kind of like Cleopatra, plus a dance label and a hip-hop label. Big Daddy had become this massive distribution hub for various genres – their whole business was built around having all these different outfits constantly feeding them product to push into retail.

What did Big Daddy think of MAYHEM?

PAUL: I presented the album on location in New Jersey – even showed them a video Michael sent me of MAYHEM performing live – and everyone was blown away, vowing to push it hard. My entire staff rallied behind “Grand Declaration of War”; Necropolis threw everything we had behind it.

In May 2000, only four months after the MIDEM meeting, Necropolis released the US edition of MAYHEM’s “Grand Declaration of War”. To both Paul and Michael Berberian’s profound relief, it proved a commercial success in Europe and North America alike.

PAUL: College radio picked it up, the music press responded well – despite the band’s controversial backstory – and fans, distributors, and record stores all seemed excited. Such moments are truly rare in this business; it had already happened through WITCHERY and DAWN, and then again with MAYHEM.

Hand to your heart – how much did you pay Metal Maniacs for their review?

PAUL: Honestly? Nothing. I never paid for reviews. What happens is, once you build momentum and the mainstream crowd suddenly decides you’re cool, these publications want to be associated with you – and sometimes they’ll stretch the truth. I’m not saying it happened in this case, though.

They called it ‘one of the best albums ever made’ – which, I’m sure you’ll agree, is a bit of a stretch.

PAUL: <laughs> Let’s be real; I loved the album, but it’s no “De Mysteriis…”. Some of those Metal Maniacs guys, like Jeff Wagner, went on to write books later – but back then, they were maybe twenty-five. What does anyone really know at that age? And most of them weren’t even into black metal.

I don’t recall much enthusiasm among my peers – I got the sense “Grand Declaration of War” was mainly embraced by new MAYHEM fans.

PAUL: Possibly. MARILYN MANSON’s “Mechanical Animals” (1998) had a massive impact, and that industrial edge was in the air. Naturally, “Grand Declaration of War” drew plenty of backlash from purists – as could be expected. Many didn’t even view it as the same band; they thought MAYHEM should’ve called themselves something else.

PAUL: Afterwards, Big Daddy kept saying, ‘We want another MAYHEM! Can you find us one? That’s what we need from you.’ This is how distributors think: once a title comes along and moves fifteen thousand units, they want ten more just like it. The whole thing is pure business.

log in to keep reading

The second half of this article is reserved for subscribers of the Bardo Methodology online archive. To keep reading, sign up or log in below.