Necropolis Records XV

2025-12-10

by Niklas Göransson

By 2002, the landscape surrounding Necropolis had begun to tremble. As digital currents reshaped the underground and physical sales bled away, every new release became a wager made on collapsing terms.

PAUL TYPHON: There was a sea-change underway, right? I had an inside track thanks to friends from school who ended up working at these big tech companies. They told me, ‘Paul, you really need to check out Napster.’ I installed it, messed around for a bit, and thought, ‘Holy shit.’

For a label manager, Napster must have been a sobering discovery. Launched in the Bay Area in the summer of ‘99, it quickly became the first widely used music-sharing platform.

PAUL: By 2001, they had something like eighty million users, and that shockwave caused the first real mass-scale collapse of music revenue. Metalheads were early adopters – everything was on Napster, and you could pick from all these different servers.

Almost overnight, vast swathes of underground black metal history were digitised; material that once required contacts, trades, and effort suddenly sat a click away. The first time I tried Napster, I searched for COUNTESS’ “Son of the Dragon” – a track from an obscure ‘97 EP – and found it instantly.

PAUL: The impact was profound: our CD sales plummeted immediately. All of a sudden, fans who used to pick up two or three records per week from us were grabbing MP3s online instead. If you can download the VIKING CROWN album, you’re probably not going to go buy it, right?

Famously, METALLICA became the most visible opponents of file-trading. After discovering not only their entire discography but also unreleased material circulating online, the band sued Napster, forcing them to block thousands of user accounts.

PAUL: There’s a certain bitter irony in finding yourself on the same side as Lars Ulrich <laughs>. All the kids hated METALLICA for that. Forward-thinking labels suddenly stood at a crossroads: embrace this new technology or get wiped out. Survival hinged on making the right call.

Long before the big streaming platforms appeared, eMusic – a subscription-based MP3 service founded in 1998 – began courting independent labels. Offering a small per-download fee, they licensed huge portions of underground catalogues from the likes of Metal Blade, Relapse, and Necropolis.

PAUL: I talked to Matt Jacobson (Relapse), and he said, ‘I don’t know how to handle this MP3 shit; we’re just signing with eMusic because they offered an advance we can use to press more records.’ But digital revenue in 2002 was nothing compared to CD sales, so nobody made any real money.

PAUL: Extreme metal was exploding artistically, but not economically. All these new sub-genres appeared while revenues dropped, international partners dragged their feet on payments, and marketing costs shot through the roof. Nonetheless, I kept pushing to make the label work, and we did put out more records.

In early 2002, Paul gave an interview to Metallian, addressing the various issues Necropolis faced at the time. The sudden departure of two staffers during his 2001 summer trip to Europe created not only administrative chaos but also plenty of gossip.

PAUL: By then, I’d put the company back together. Matt and Jose were still around. Dave Pirtle – the host of a metal college radio show in San Jose – had just joined. I also hired Rachel and another girl, Krista. Leon and Raul from IMPALED handled the website and sales, respectively. Everybody was all in.

Unsurprisingly, the interview’s focal point was on Necropolis’ supposed demise. Paul dismissed any talk of bankruptcy, framing the staff exits as logistical setbacks rather than a death knell.

PAUL: You know how the rumour mill spins: ‘Oh, what’s going on with this label?’ Meanwhile, Necropolis kept operating just fine. And 2002 brought the Century Media deal, which I saw as the solution to pretty much all our immediate problems – soup to nuts.

The Metallian article also noted that after two years of Baphomet releases, Paul’s interest had faded. Fueled Up was essentially wound down, citing difficulties in marketing punk rock to their metal customer base. More importantly, Necropolis announced that European distribution would now be handled by Century Media.

PAUL: The two partners at Century Media, Robert and Oliver, had known me long enough to understand my drive and tenacity. Funnily enough, it was our deathgrind venture that sealed the deal. They were impressed by how we’d handled ROTTEN SOUND – built up the brand, sold a good number of records, and got them on the road. Same with WITCHERY, DAWN, and so on.

While moving through the Bay Area grind and crust scene, Paul heard about a Finnish grindcore act searching for a label. After checking out ROTTEN SOUND, he signed them to Deathvomit and released the “Still Psycho” mini-CD in 2000. Not long after, they teamed up with IN AETERNUM for a European run opening for MALEVOLENT CREATION.

At the time the Century Media deal went through, Deathvomit was preparing to release ROTTEN SOUND’s third full-length, “Murderworks”.

PAUL: That’s when Relapse tried to steal ROTTEN SOUND from us. Matt even called me, saying, ‘Oh, your label is going to shit, what are you going to do?’ – just being a complete asshole. And I thought, ‘Oh, so this is how the Relapse–Necropolis merger would’ve played out?’

Years earlier, Relapse had approached Paul about folding Necropolis into their operation. Hoping to attract bands like CRADLE OF FILTH, Jacobson felt they had the infrastructure but lacked black metal credibility.

PAUL: I’d done perfectly fine without them and proved myself to the industry – the Century Media deal made that obvious. And finally, after all those years, we had the pressing-and-distribution deal I always wanted. Once the agreement was in place, I wouldn’t have to stress about every little detail anymore.

Amid industry upheaval and under mounting pressure from distributors, Necropolis issued one of its biggest titles in years – the US edition of DARK FUNERAL’s “Diabolis Interium”.

PAUL: During our contract negotiations, Ahriman brought up touring the US as one of their demands. So, I put in a clause – ‘If you sell 10,000 albums and they don’t get returned, then we’ll support your tour.’ The problems started when DARK FUNERAL wanted to hit the road immediately.

Soon after the autumn 2001 release of “Diabolis Interium”, the Swedes were invited to support CANNIBAL CORPSE on a month-long North American tour.

By then, CANNIBAL CORPSE were arguably the world’s biggest death metal band; their 1994 album “The Bleeding” had moved almost 100,000 copies in the US, making it one of the genre’s top sellers. For a European black metal act, sharing a bill with a group of that stature meant massive exposure – and equally massive expenses.

PAUL: Fascinating how these opportunities always show up when you least anticipate them, eh? And as a label, you’re expected to accommodate – so once again, I was stuck between a rock and a hard place. I needed sales revenue to cover tour support, which is why I structured our agreement the way I did. They insisted I back the tour regardless.

How much money are we talking about?

PAUL: Another ten to fifteen grand or something ridiculous. With everything going on, it was a terrible time to attempt all that. Meanwhile, import copies of “Diabolis Interium” were pouring in – so yeah, my old EMPEROR hustle came back to bite me in the ass and undercut our sales.

Back in 1997, leading up to EMPEROR’s “Anthems to the Welkin at Dusk”, Paul struck a deal with Steve Beatty of Plastic Head Distribution. As soon as Candlelight released it – two months before Century Black put out their US edition – Necropolis flooded American stores with three thousand import copies.

PAUL: When the tour offer came, we needed to move another 7,500 copies. My big gripe – and I hate for it to sound like a technicality – is the difference between shipped and sold. Just because I’d sent Big Daddy 10,000 records doesn’t mean anyone actually bought them. But Ahriman refused to let it go.

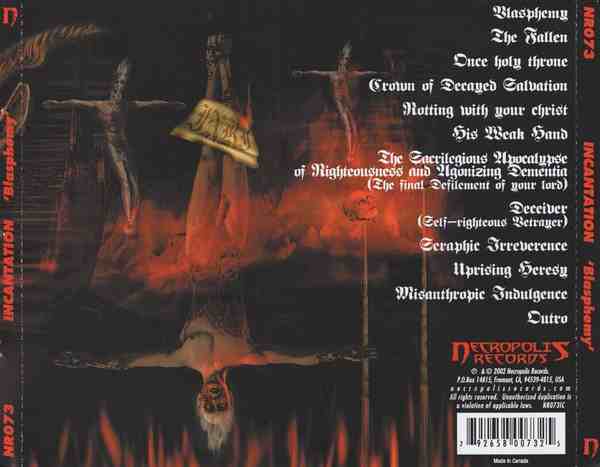

In January 2002, INCANTATION were announced as part of CANNIBAL CORPSE and DARK FUNERAL’s upcoming thirty-day North American tour. In a statement, John McEntee described it as a great opportunity to support their ‘latest and most sacrilegious album to date, “Blasphemy”, for Necropolis Records’.

When the tour began in April 2002, however, the album was still unreleased.

PAUL: I’d have to go back and check the release schedule. History tends to twist these things, but my track record is very clear, right? I’m not sending a band on tour without a new record; I’d never do that. If the date slipped, it was probably because of our US distributor, Big Daddy.

In an interview with Voices from the Darkside, John McEntee blamed the delay on financial trouble surfacing at Necropolis just as INCANTATION entered Cleveland’s Mars Studio in the summer of 2001. They tracked the basics, then supposedly had to pause, returning only when more funds appeared – resulting in four separate sessions over six months.

PAUL: Not really true. One thing to remember: they were a working band. Those guys all had jobs and couldn’t sit in a studio for four straight weeks. John is one of the few guys I really respect – he’s usually honest and humble about what he’s created – but that was still a shitty comment to make.

“Blasphemy” finally landed in June 2002, two months after the tour. True to their style, INCANTATION’s sixth studio album offers suffocating death/doom riffing swirling around stark tempo shifts to build a murky, oppressive atmosphere.

The ambient outros were apparently added as a jab at Relapse, who’d encouraged the band to ‘experiment more’ during their earlier tenure.

PAUL: I didn’t know they intentionally pissed off Relapse – but if so, great. I still think “Blasphemy” is one of their best records; it felt like a return to the roots and that early spirit of bands like INCANTATION, PROFANATICA, and IMMOLATION. Still, 2002 might not have been the ideal time to release dark, ritualistic death metal.

Around 2002, the landscape for heavier, traditional death metal had shifted noticeably. The late ‘90s splintered the genre in several directions – melodic Gothenburg bands edging into the mainstream, ultra-technical styles rising through labels like Unique Leader, while deathgrind dominated the underground.

PAUL: We printed tonnes of promo material and sent out CDs to radio stations and magazines well in advance so they could give it the full pre-release blitz. Nike even wanted to feature INCANTATION in a skateboarding commercial, believe it or not. I don’t know if you can still find it.

I’ve heard about this but never seen it. I can find mentions online, but not the ad itself.

PAUL: Shows you how big the endorsements can get once you’re running both a label and a publishing company. Still, even with a huge push, “Blasphemy” ended up just another blip on the radar. As much as I hate this stupid ‘Necropolis curse’ idea – that’s exactly what it felt like.

In the Metallian interview from early 2002, Paul denied rumours of BABYLON WHORES having split up – insisting the announced “Death of the West” album would appear on Necropolis that summer.

PAUL: That was the plan, right? I can’t remember every detail, but we came really close to releasing the album. It might’ve been the studio, or just the general state of Necropolis at the time – too many fires to put out. Spinefarm stepped in, so we probably asked them to take over.

Speaking to Invisible Oranges for a 2014 retrospective, BABYLON WHORES frontman Ike Vil said the recording coincided with a period when Necropolis was already struggling. Once the sessions were underway, it became clear the label wouldn’t be able to follow through, so they sold the master to Spinefarm.

PAUL: Right. Chalk that one up to the financial realities of 2002. It’s tragic, because I loved those guys. Not coming through on “Death of the West” is a big regret – BABYLON WHORES were one of my favourite bands on the label. Even King Diamond liked them, which was great to hear.

In the Invisible Oranges piece, Ike Vil mentioned that ‘Necro-Paul got us to support King Diamond’ on the extensive North American “House of God” tour in August 2000.

PAUL: Expensive as hell, but I’d been waiting so long for such opportunities to line up that it felt wrong not to back my bands when something finally happened. Two years later, with “Death of the West”, I simply couldn’t give BABYLON WHORES proper distribution. Retail was dying in the States.

PAUL: The Full Moon interview brought up some interesting points about 9/11. That day terrified the American public like nothing else – people were literally afraid to leave their homes, and the whole country felt weird. It hit travel and tourism immediately, triggering a nationwide spending freeze.

Jon Thorns recalled the events on September 11, 2001, as the blow Full Moon Productions never recovered from. Their US distributor, Dutch East India, went under in the aftermath – with thousands of F.M.P. titles still in its warehouse.

PAUL: Discretionary spending on CDs vanished as foot traffic in stores dropped, so retailers cut their orders and sent back more product. Touring suffered too – insurance costs shot up, fewer bands hit the road, and releases were delayed because of market uncertainty. Then came the major-label layoffs, which flooded record shops with promos and cut-outs.

As the majors downsized, excess stock leaked out from every direction. Offices were cleared, leaving piles of promos, advances, and back-catalogue titles that departing staff dumped into second-hand shops and flea markets. At the same time, warehouse overstock was unloaded in bulk to liquidation wholesalers, who sold brand-new CDs to retailers for a dollar or two.

PAUL: The retail collapse was in full swing. You could feel it everywhere: indie shops were fighting for their lives, and the big chains wobbled right beside them. The Wherehouse, Tower Records, Sam Goody, Virgin Megastore – all bleeding money, slowly dying.

Metal got hit especially hard. Once demand for niche imports evaporated, the independent stores that normally carried underground music died off en masse, leaving distributors like Dutch East India and Big Daddy buckling under the weight of lost accounts.

PAUL: Big Daddy expanded like crazy in the ‘90s – especially in punk, hardcore, and metal. But they overordered inventory and got crushed when the returns piled up. So, now owing various labels hundreds of thousands of dollars, those New Jersey jokers go, ‘Oops, we didn’t see this coming!’ while I’m thinking, ‘Well, you’re fucking up my whole business here.’

Didn’t you get any money?

PAUL: Month after month, they’d send a pittance – basically just enough for us to cover rent and salaries. Whatever was left went straight into pressing more stock, which is exactly how they wanted it: ‘Here’s a little something, but don’t spend it on anything except making us more CDs.’

Was there any other distributor you could’ve turned to?

PAUL: Too late for that; most had already abandoned indie music. Caroline Distribution consolidated its lines, effectively killing support for small labels. Valley shut down completely; Revolver USA survived but slowed to a crawl… and I’m pretty sure Lumberjack cut way back on independent titles.

log in to keep reading

The second half of this article is reserved for subscribers of the Bardo Methodology online archive. To keep reading, sign up or log in below.