Árstíðir lífsins

2019-06-12

by Niklas Göransson

Árstíðir lífsins is a German-Icelandic trio performing metal music infused with Old Norse concepts. With a knowledge base firmly rooted in academia, guitarist Stefán discusses historical mysteries, dead languages, and Skaldic riddles.

– The interplay between our artwork, music, and lyrics – regardless if they are in Old Norse-Icelandic or their English translations – is of the utmost importance. Only in the combination of all three parts do we feel as if we’re able to deliver that which is intended with an ÁRSTÍÐIR LÍFSINS release. So, needless to say, I’m not particularly fond of this current-day development towards an increasingly digital music distribution.

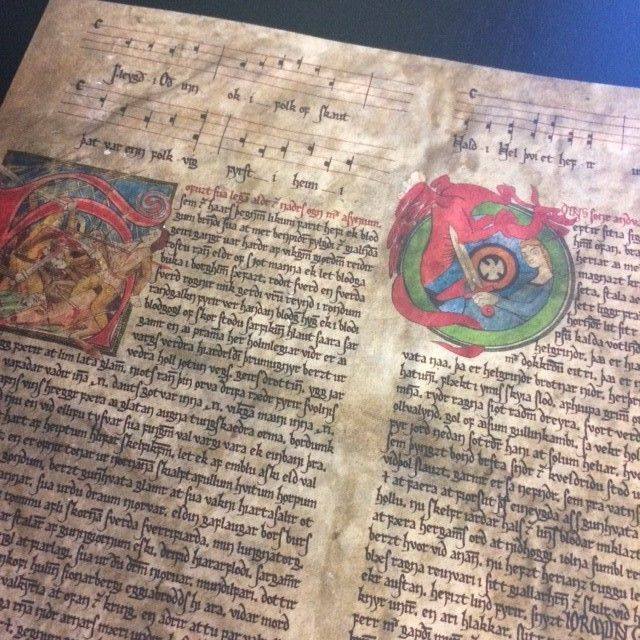

This is abundantly clear for anyone who’s seen ÁRSTÍÐIR LÍFSINS’ physical releases. Their highly ambitious booklets typically feature the lyrics presented in a manner that resembles original medieval manuscripts along with English translations, a plethora of historical references, artwork, and various other details; somewhat more conceptual depth than what’s usually lumped in with pagan and folk metal. As far as these connotations go, my impressions place them closer to PRIMORDIAL than genre-associated acts of the more yodelling variety.

– Oh yes, the so-called pagan metal music. While I’m very happy with PRIMORDIAL references, especially given their iconic “Spirit the Earth Aflame” album, I find nothing enjoyable about these humpty-dumpty party metal bands. There’s nothing to be gained from such acts, neither music nor lyric-wise. I’m quite certain PRIMORDIAL feel the same way. A BATHORY influence to our music is undeniable and I have no problem with comparisons to Norwegian bands incorporating Old Norse concepts, such as HELHEIM and ENSLAVED, or our brothers-in-arms HELRUNAR. However, the vast majority of bands dealing with Viking Age topics these days are anything but interesting and, quite frankly, a complete waste of my time.

The latest album by ÁRSTÍÐIR LÍFSINS, “Saga á tveim tungum I: Vápn ok viðr” – just rolls off one’s tongue, doesn’t it? – was released by Ván Records in April 2019.

– Just like our previous outputs, the newest record deals with parts of the Viking Age as seen through primary vernacular sources such as Skaldic and Eddic poetry, parts of the renowned saga literature, as well as select archaeological findings and religious medieval art. Every ÁRSTÍÐIR LÍFSINS record is thematically linked and features nine songs each, all of which are named after the first sentence of their respective lyric. In both musical and lyrical terms, the newest album is our most advanced by far. We used a lot of 11th-century Skaldic poetry composed in the direct surroundings of King Óláfr Haraldsson and then, to emphasise the religious zealotry of the story’s main character, combined it with a number of strongly Christian-inspired Icelandic vernacular poems dating back to the same time. The music also features a lot of choral arrangements which fit in perfectly with the religious content of its poetry. As on the previous records, we wanted to depict the bloodlust and brutality of battle in a similarly clear and somewhat sadistic way – through the eyes of contemporary-medieval skalds.

Árstíðir lífsins is Modern Icelandic and means ‘The Seasons of Life’. Stefán says the band’s name stems from a greater concept and is closely related to the inherent structure of their records.

– The name serves as an umbrella-concept for most of our album themes, in that a protagonist is born during late winter and lives his life throughout the change of seasons. Finally, he dies again by season’s end – the winter of his life, metaphorically speaking. The setting is continuous, which is why the end of each album always indicates what to expect from the next one. All of our records are connected in the sense that they depict the life of one generation of an entirely fictive family narrative set against the background of a specific historical event in the Viking-Age era West Atlantic world. Thus, while the actual album protagonists may never have existed, the actual time and place they’re set in certainly did. And this period is depicted through both lyrics and layout in a very accurate, scholarly way based on a lot of prior research.

And this is where the academic acumen of all three band members come in – German vocalist Marsél has a Magister Artium in Cultural Anthropology, Nordic Philology, and History from the Westfälische-Wilhelms-Universität in Münster, Germany. Icelandic drummer Árni has a BA in Composition from the Listaháskóli Íslands in Reykjavík, Iceland, and is currently finishing his MA studies in Composition at Sweden’s Gothenburg University.

– I studied Nordic Philology, History of Art, and Philosophy as Magister Artium at the University of Kiel in my native Germany. As part of this program, I went to Reykjavík as an exchange student and earned a Master of Arts in Medieval Icelandic Studies. It was during my stay there ÁRSTÍÐIR LÍFSINS was born and also when we composed and almost completed our first album, the 2010 “Jǫtunheima dolgferð”. After finishing in Kiel, I went on to write my PhD – in Scandinavian Studies again – at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. After defending my PhD, I moved to Frankfurt am Main in Germany and worked freelance as part of an editorial project dedicated to Eddic poetry until I was offered the position of research associate for Old Norse Studies at the University of Greifswald. That’s where I’m currently at, Greifswald, I teach Old Norse language and literature here. This coming autumn, I’m moving to the University of Bergen, Norway, to become a postdoctoral research fellow in Medieval Studies. My main academic interests lie in the scholarly fields of Old Norse philology and art history, with the illuminated manuscript cultures of medieval Iceland and Norway as main subject.

I read that you studied Old Icelandic – one would have to be pretty passionate about the subject matter to learn a dead language?

– I became strongly interested in Old Icelandic around 2006, during my time in Kiel. The language flows really well together with the literature and poetry expressed through it. Even on the often rather limited text on runestones or rune graffiti in stave churches, Old Norse in written literature really becomes somewhat of a timeless tongue – probably comparable to Old Greek and Latin for those more familiar with these beautiful, similarly dead languages.

Whilst conversing about Norse esoteric traditions with Sturla Viðar of SVARTIDAUÐI, he brought to my attention Icelandic scholar and poet Jochum ‘Skuggi’ Eggertsson, who had some rather radical theories pertaining to Icelandic history. Skuggi is perhaps mostly known internationally for Galdraskræða Skugga, a collection of texts he gathered whilst travelling all over Iceland on a mission to copy every grimoire he could lay his hands on. The result was published in 1940 and later released internationally as Sorcerer’s Screed: The Icelandic Book of Magic Spells.

– I’m not particularly interested in esoteric literature. What I find compelling is the medieval mythological corpus of Old Norse-Icelandic literature. As is well known, in the end this comes down to only a few texts, manuscripts, and select writings on runestones. I’ve never been fond of Skuggi’s work, mainly due to the highly dubious theories he established. However, a friend of mine from Iceland is currently delving into these writings and starting to reproach them with a more modern view. Although this clearly falls outside my scope and scholarly interest, I look forward to what he has to say once his research is completed.

After revising the body of literature he’d gathered, Eggertsson concluded that when the Nordic refugees first arrived in the 9th century, southern Iceland was already populated by Celts. Furthermore, Skuggi claimed these Celts were the real creators of the Eddas, Vǫluspá, and most of the Icelandic sagas. Having found the theories somewhat outlandish but rather intriguing, I tried researching them myself but didn’t get very far due to the lack of English source material. This is where it’s convenient to have at hand an Icelandic-speaking scholar specialised in the subject matter.

– I’m aware of the theory but, as you may already expect, I’m not convinced by it at all. The primary writing Skuggi refers to is obviously the famous Íslendingabók, which was initially written by what’s very likely Scandinavia’s first historian writing in vernacular, Ari fróði Þorgilsson, some 250 years after Nordic settlers arrived and drove off – or so says the legend – these so-called papar who are said to have lived in caves scattered around Iceland’s southern parts. Íslendingabók further states that these well-educated hermits, most likely of Scottish or Irish descent, left behind bells, Irish books, and croziers. Supposedly, they departed out of refusal to live alongside the heathen settlers who arrived on their shores in the early 870s. Neither these books, bells, nor the croziers have been found so far. In addition, a reference to Eddic poetry and the Sagas of Icelanders is nothing but wild speculation. Finally, medieval naval travel stories set in the north about Saint Brendan of Clonfert and other Irish saints are first and foremost of fantastic nature and barely supported by any factual evidence. Thus, Skuggi’s theories are just fantasies without relevance.

Skuggi claimed these Celtic hermits were so-called Krýsar, where did he get that idea from?

– From the name of a place called Krýsuvík on the south-western Icelandic Reykjanes peninsula. As it happens, the area got its name from a local legend about a woman named Krýs and not from any hermit settlers. These papar have two further medieval references implying that the land had already been Christianised before the heathen settlers became Christian some 130 years later. Furthermore, the overall structure of Íslendingabók shows a similar structure, both in content and argumentation, as parts of the Roman letters of St Paul, which similarly directs the reader to the coming of Christ and thus the arrival of Christian society in Iceland. While I have no doubts that early Irish or Scottish hermits inhabited some caves in southern Iceland prior to the permanent settlements, it must be said that Skuggi completely ignores the cultural pre-setting of Íslendingabók and builds his hypotheses on what I can only assume to be completely unknown followers of one of the Fathers of Christendom: the late 4th century Archbishop of Constantinople, and saint, John Chrysostom. Archbishop John was an excellent preacher – probably what his epithet refers to, as it translates to ‘golden-mouthed’ in Old Greek – a very active writer of homilies and a fierce politician. However, his writings never had a strong importance for western Christendom, and any links to ecclesiastical followers in the history of early Iceland are completely unknown.

The primary reason I took some interest in these claims is that since Eggertsson’s death in 1966, peculiar carbon-dating results have emerged from various ancient sites. One example is the Kverkhellir cave, considered Iceland’s oldest known archaeological site, estimated to have been constructed around 800 AD – almost seventy years before any northern settlers arrived. Some Icelandic archaeologists now believe its residents to have been Christian monks on a Hiberno-Scottish mission.

– I know the Kverkhellir cave well and am familiar with the current news from the archaeologists on the dating results. I have nothing against these theories, of course, as it may well be that hermits from Scotland and Ireland lived in Iceland before the first settlers arrived. Some of these sites are filled with carved crosses – however, almost all of these carvings were added much later by pilgrims in early modern times. In addition, such stone carvings are simply not securely datable.

What really confused me in this context was the 2001 mitochondrial DNA study which showed that as much as sixty-two percent of the original female settlers had ancestral roots in the British Isles. This would suggest some manner of Celtic presence. Then there’s the latter-year linguistic research which has shown many areas, volcanos, and rivers to have names which cannot be traced to any Nordic tongue. The same goes for parts of the Icelandic language itself.

– I am not a specialist in Old Norse volcanos but, so far, I’ve not come across a large number of names which don’t sound particularly specific to the Old Norse poetic language. This DNA-reference is built upon the fact that many females from Scotland and Ireland came to Iceland along with the original Norwegian settlers. Apart from the mentioned Íslendingabók, the country’s early history can be studied in the famous Sagas of Icelanders – an exclusively verbal tradition until transcribed sometime in the early 13th century.

As I was going through my notes on this topic, I remembered my discussion with Einar Selvik of WARDRUNA about the Norse poetic metre called dróttkvætt. Perhaps relevant to this purported Celtic connection is how the dróttkvætt is not only significantly more complex than any other Skaldic craft found in the Germanic language family, but also has far more in common with Irish and Welsh lyrical traditions. I should reiterate here that I’m personally not advocating any Celtic theories, I have no idea what to make of any of this – hence why I’m keen to ask a scholar about it.

– The dróttkvætt is, at least content-wise, very wild at times but also highly strict in regards to its rhyme pattern – in fact, stricter than any other Germanic poetic metre. Should any names that sound odd appear here, I’d assume their wording was changed to better fit the pattern of that particular stanza. Either way, loan-words from other parts of western and northern Europe in particular are fairly common in Old Icelandic and exemplify the international nature of the earliest settlers quite well.

The following is an excerpt from Grímnismál, one of the mythological poems in the Poetic Edda:

Fimm hundruð dura ok um fiórum tøgum,

svá hygg ek at Valhǫllo vera;

átta hundruð einheria ganga ór einom durom,

þá er þeir fara at vitni at vega.

This translates roughly to, ’Five hundred doors and forty, I think there are in Valhǫll. Eight hundred Einheriar will pass through a single door when they march out to fight the wolf.’ 540 times 800 means 432,000 warriors rising to the occasion. As was discussed at some length with ALTAR OF PERVERSION, VANUM, and PHURPA, the number 432 has an insane prevalence in wide-ranging realms such as spirituality, nature, music, and science. Perhaps most relevant in this context is its occurrence throughout various religious traditions – for example Sumerian, Babylonian, and Tibetan spirituality as well as Buddhism and Hinduism. I wonder if Stefán has ever reflected over this number, and how the hell it ended up in a 13th century Icelandic text. And yes, I’m aware that in Germanic languages up until the 15th century the term ‘hundred’ was used for six score, which is 120. Nevertheless, semantic specifics aside, the number is still there.

– This definition of ‘hundred’ is important to remember, since it’s unverified whether the numbers 100 or 120 are referred to here. Nonetheless, the presence of this recounting number in an Old Norse source in relation to the older examples is indeed unusual. I know that in research on Eddic poetry and Old Norse mythology, the named numbers in Grímnismál are considered ‘very large numbers’ and refer to the massive dimension of Valhǫll: Óðinn’s hall of the slain. Another theory suggests that the concept of Valhǫll’s many doors refers to knowledge of Roman amphitheatres. Either way, apart from famous examples such as three, nine, and so forth, in quite many cases numbers in vernacular Norse poetry hold no particular relevance for the content. Just as an example, the alliterations of the numbers in question – the stressed F in fimm, fjórum and the stressed vowel in átta, einheria, einom – are clearly contributing to the stanza‘s inner rhyme pattern.

An alliteration means that the subsequent words, or ones closely connected, start with the same letter or a similar sound – such as with the stressed F and vowel in the Grímnismál example. Alliterations are integral to verbal traditions as they bring a musical quality to the recital, making it more attractive to listeners and easier for skalds to memorise. As with many stanzas in Grímnismál, stanza 23 follows an Eddic-specific alliterative verse-form called ljóðaháttr; it’s less complex than dróttkvætt but still requires masterful linguistic skills to compose.

– Consequently, the actual number may be less important for the content. With the present example I hardly see a particular historical or societal connection to your other examples. I also suspect its mathematical background is not connected to any known medieval Icelandic numeric treatises such as calendars and, generally, the rather famous Alfræði íslenzk collection. Furthermore, in the Grímnismál stanza itself, the numbers are not multiplied so the number of Einheriar remain unknown to the reader.

With Stefan included, I have now presented this Eddic numerological curiosity to three different academic scholars of Old Norse; all have reacted similarly, essentially writing it off as a freak coincidence. Taking my interviewee’s suggestion that it might’ve sprung from a necessity of adhering to the poetic metre; let us for the sake of argument say that this is entirely correct. Statistically speaking though, surely it would be spectacularly improbable that the exact same six-digit number ends up – by sheer chance – in both the Poetic Edda and the sacred Hindu scripture known as Rg Veda? It’s even hard-coded into the latter, the world’s oldest known written work, with its exactly 432,000 syllables. Add to that all the remaining examples from across the globe and it should be difficult for even the most reasonable of minds mind to rationalise. While I really have no clue what any of this means, I struggle coming to terms with notions of it merely being a string of numerological happenstance.

– Admittedly, I have no knowledge about the other references you mentioned. However, it’s hard for me to see a clear reference between Grímnismál stanza 23 and the much older sources from far distant places. Note that Grímnismál is tentatively dated to the late 12th or even early 13th century, some two hundred years after Iceland was Christianised. And, as I said, various numbers appear here and there in Eddic poetry; in Grímnismál alone there are several such mentions where they are clearly included to keep the story going. Although the result of 500 plus 40 times 800 is a surprise, this number 432,000 is not outright mentioned in the poetry itself and, to me, the stanza does not indicate the numbers are meant to be multiplied. This is also somewhat contrary to the content, in my humble opinion. In addition, the number 500 is mentioned in the previous stanza of Grímnismál too, without any obvious numeric relevance.

Disregarding all the remaining exotic examples, could the Vedic link have something to do with shared Indo-European roots?

– I find it highly unlikely that there are any ‘Indo-European roots’ to be found in this particular stanza. In the scholarship of Old Norse religion, however, similar ideas appear now and then but, I have to admit, I was never too happy with such comparisons. Most of those theories consist a bit too much on sheer guesswork, with too little factual value for my taste. But one doesn’t have to concur on everything – in fact, it’s quite normal to disagree in the Humanities.

What’s next for ÁRSTÍÐIR LÍFSINS?

– We will release the second part of “Saga á tveim tungum” later this year, as well as a split release with a certain Icelandic black metal band you might be familiar with – they’re playing at the Ascension MMXIX festival. Both releases will, as always, be handled by the great Ván Records. Apart from the already recorded material, an EP once again dealing with mythological topics is planned for some time in the distant future, but no music or lyrics have been written thus far. As it stands now, it’s unlikely that we’ll start working on the EP before autumn.