Aversio Humanitatis

2021-02-17

by Niklas Göransson

Blackened eyes that patiently watch. S.D. of Aversio Humanitatis discusses his personal backstory – an upheaval of body and mind which would have crushed the spirits of lesser men.

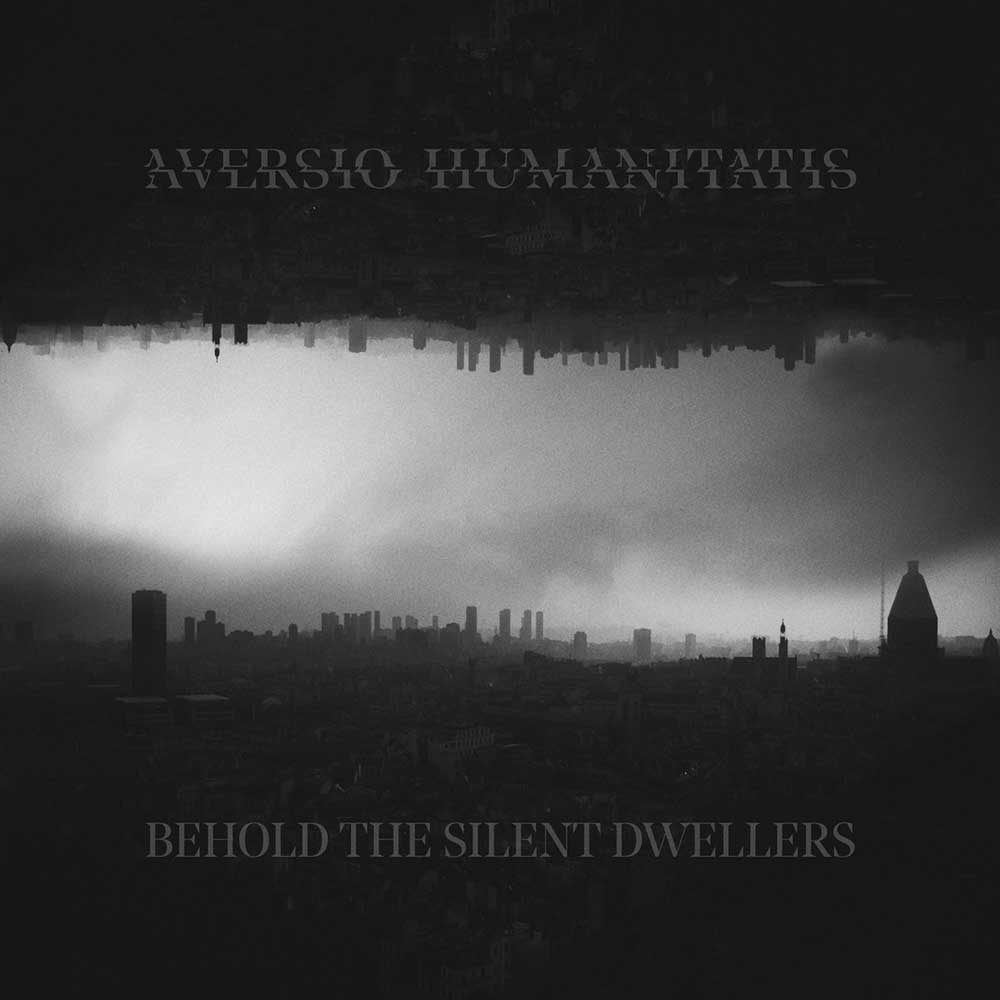

– I was recently talking to this guy from a band called PRIMEVAL WELL – they play an interesting and well-accomplished blend of black metal with Americana folk influences, When you listen to their music, you can feel its connection with nature, with the roots of a certain location, and with the past. Well, “Behold the Silent Dwellers” could be regarded as an antagonist to all this. It’s like being plugged into a socket in an endless concrete wall stretching across the entire horizon; both reality and present falling on your shoulders. Our work has no bonds with a specific time or place, just bad news and ominous foreboding. Perhaps there is a longing for those connections somewhere in the background, but the underlying feeling of both the album and the band is like being out of place and in a process of constant depersonalisation or dehumanisation.

“Behold the Silent Dwellers” was released by Debemur Morti Productions in June 2020. Contrary to the previous work of AVERSIO HUMANITATIS – the 2017 mini-CD “Longing for the Untold” – their new record was borne out of a collective rehearsal effort. I’d like to think there’s an added dynamic to a music piece that’s been cultivated in a practice room, rather than computer files emailed back and forth.

– I’m not sure the result would’ve been too different – however, at least composing like this felt more rewarding. There’s definitely a different energy and a greater sense of belonging to the band on everyone’s part. At the end of the day, it’s always necessary to do some work at home, make changes and arrangements, and then revisit the compositions to listen from the ‘outside’. Still, the work performed in the rehearsal room feels more like the real thing. Once in a while, it’s good to look away from a computer screen and actually play, sweat, and enjoy the music.

The production is a piece of art in and of itself – it sounds like the cover looks. S.D. is a studio engineer and works full-time running his own Madrid-based operation, The Empty Hall Studio. Not only having access to professional recording facilities but also the know-how to properly produce, mix, and master the result must be amazing in terms of capturing one’s initial vision.

– Yes, it’s definitely an advantage from a creative and organisational point of view. We arrange the recording sessions as best suits us and I can work on the sounds I have in my head with no need for transcribing ideas into words in an attempt to explain them to someone else. Some of these projects reap more success than others, as there are limits both to my studio and professional experience. But, generally speaking, we are very pleased with the results achieved.

In a 2020 conversation with Phil Kusabs from VASSAFOR, he spoke about what a mindfuck it is to produce one’s own albums. Most musicians are pretty fed up with their material by the time it’s been thoroughly rehearsed and then recorded – and that’s when they rely on a studio engineer for the painstaking process of bringing some order to the sonic chaos by way of mixing and mastering.

– I get sick of both our own and other people’s songs all the time, it’s part of the job. By now, I’ve developed the ability to work countless hours on an album without really ‘listening’ to it; meaning, I completely ignore whether I like the music anymore. I listen to it in a mechanical way rather than for enjoyment, trying to make every part sound as good as possible. I mainly use this approach during the early stages of recording and mixing – but once the process has advanced to a later phase, I resume listening from an artistic perspective.

When performing final proofreadings of one’s own articles – scrutinising text one almost knows by heart at that point – it can be challenging to remain focused and attentive. I suspect something similar occurs during the tail-end of a music recording, so I’m wondering if S.D. has developed any useful tricks.

– I wish I had a foolproof technique of doing this as safely and as fast as possible, but I don’t. I use the traditional way of having a checklist of steps ensuring that all the files are correct. I manually check everything three or four times and then, finally, ask the other people involved to also give it a listen. I try to designate a window of time to do all of this, but often fail miserably and end up spending hours more than it should take. However, there’s no choice but to do this exhaustively because once the vinyl is pressed and CDs are duplicated, the damage has been done. Such eventualities are the very fabric of nightmares for me… the mere thought of fucking up the track-list or leaving gaps or clicks in the middle of a song – and then, suddenly, there are hundreds of useless physical copies of the record with all the blame on me.

A musician I interviewed last year, Finian from IFERNACH, is a classically trained guitarist. When I asked what advantages he draws from this, he said, ‘I can compose songs in my head without touching my guitar. I know where the notes are and how they sound without playing. I can read music.’ It occurred to me that there might be an equivalent for studio engineers – for example, hearing a rough demo but envisioning it properly recorded and mixed.

– In strictly musical terms, there’s nothing similar going on in my head. My knowledge of music theory is basic and limited; I compose very intuitively, through trial and error. So, I must have a guitar in my hands to create a song. This is not the best way, but it’s the one I use for now. One of my mid-term goals is to broaden my theoretical knowledge of music and gain a better understanding of how it ‘works’. But, beyond this, I have other resources to discern which ideas have potential and which are not worth developing further – such as having a couple of simple riffs in my head and being able to visualise their final sound on a finished recording. I suppose this is the ultimate goal of any musician: to create efficiently, to transcribe anything from the imagination into the real world, and knowing how to develop raw or isolated ideas to get the most out of them. It’s a hard and long road, and I can’t say that I’m always successful.

Besides everything pertaining to the music and its recording, AVERSIO HUMANITATIS also handle all aspects of their visual representation in-house. Bass player and vocalist A.M. is responsible for both photography and design.

– We’re more interested in the satisfaction of having made the best album possible than being able to say, ‘We did everything by ourselves’. If we had to enlist other people to achieve the desired quality on a certain part of the record, we would – but it just so happens that members work with these things outside the band, which allows us to take control over everything. We’re very proud of the fact that every single detail of “Behold the Silent Dwellers” has been created by ourselves.

The lyrics of AVERSIO HUMANITATIS speak of a nihilistic and deeply cynical outlook. Case in point, the actual band name means ‘To leave humanity behind’. I wouldn’t be surprised if there is precedent for this to be found in S.D.’s personal background. For starters, he lived in Venezuela until the age of sixteen. For those interested in an extensive first-hand account of the country’s decline into chaos, see the recent Bardo Methodology feature with N of SELBST.

– I’m aware of your conversation with N; him and I have been friends ever since he asked me to mix his first demo about ten years ago. We’ve remained in uninterrupted contact for all these years, so I perfectly remember his struggles to leave the country. But yes, definitely – growing up in one of the most violent cities in the world sure teaches you how things work in this life. Countless murders, kidnappings, cops who are also hitmen, paramilitary and criminal gangs financed by political parties and cheered on by many. There are no rules: children, the elderly, entire families… anything goes and nothing is punished. Caracas is definitely a ‘hot’ city.

When S.D. left the country in 2004, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela had been in power for five years. Whereas nowhere near as bad as it became over the last decade, the situation kept growing increasingly volatile.

– The country was already rotten to the core, but the irruption of the communist mindset and its way of exercising power metastasised all the cancers that were already festering. You could literally feel the country approaching the cliff – violence and corruption unleashed with impunity on all levels. And what’s more, it was being promoted by the government. They allowed the chaos to reign free, all the while silently implementing various ‘security measures’ to solidify their power: a formula we all know by now. So, yeah, my parents concluded that it would be for the best to get out as soon as possible: the longer you wait, the worse your leaving conditions. These migrations have been repeating over and over all throughout history; people have always moved from one place to another. Most of my grandparents left Portugal and Spain over economic or political concerns, and now my parents and I are ‘back’ here, for similar reasons, just a generation later. Humanity truly is one endless cycle of misery. But all this relativisation doesn’t prevent the situation from being a big pain in the ass that never stops complicating your life in one way or another. Those animals destroyed the lives of millions with a smile on their face. This has definitely conditioned the way I perceive humanity and filled me with a lot of hatred, something I find deeply regrettable.

Another chapter in S.D.’s personal history that will undoubtedly have been highly formative was a 2013 accident in which he suffered extreme trauma to his body.

– The impact fractured my skull and spine at different places; many ribs were also cracked in the combo. This affected my spinal cord and left me unable to move or even feel my body beneath the chest ever again. Of course, this was a breaking point in my life where I almost had to start from scratch again. The first four years were extremely tough, mentally. The thought of everything I’d lost which could never be regained, as well as all the things I won’t be able to either experience again or try for the first time… it would fill me with intense nausea. Being in my early twenties, this was too much to process and accept at the same time. It was like attending my own funeral whilst still alive: a sensation that really defies description. I knew there was no way to fix it, but the scenario was so bad and unexpected that my subconscious kept feeding me ideas of how it couldn’t possibly be true – that there must be some way to amend the situation. But, of course, there wasn’t. At some point in their lives, everyone must understand that sometimes there really isn’t a second chance. This particular lesson is one I learned the hard way.

Do you think having spent your childhood in a place like Caracas helped you process all this?

– Of course, after growing up in a city where anyone can get shot in the head for any absurd reason, I was already aware that the world was never meant to be a fair place. That your life is devoid of meaning and can end or get fucked beyond repair in a split second, at any moment. Nonetheless, it’s one thing to acknowledge this when you see other people’s lives being ruined, but a very different thing to rationalise when it happens to you. So, this was undoubtedly confirmation of many things I already believed: you are not special, no matter what you think you deserve. Your feelings mean absolutely nothing. Accepting and internalising this leaves you in a very fragile and hopeless situation at first, but it eventually becomes hugely liberating. My suffering is neither unique nor especially important; regarded from a non-human perspective, life and death are very similar states. There isn’t really anything too important to care about. I’m aware that pushing this philosophy to the last consequences brings you to a dead-end – one where you either have to kill yourself or force your death indirectly – but for the most part I find it applicable.

It is at least both heartening and inspirational to see how S.D. has refused to allow this turn of events to stand in the way of achieving his artistic and professional goals. I imagine it would be a daily trench-warfare against bitterness and resentment, seeing people in full health but who do not make the most of it.

– Bitterness and resentment aren’t at all words that can describe my everyday thoughts, at least not for the reasons you’ve mentioned. I enjoy and despise life as much as before. My physical predicament might be a curse, but it also led me to some sort of existential liberation. The way I approach problems and try to solve them has probably changed significantly, mostly for practical reasons. I can’t distinguish what comes down to ageing and what derives from the paralysis, but, overall, I feel the whole thing has made me more analytical and developed my personality in a way that’s less dependent on my body or physical presence. Then again, perhaps that’s just what my brain wants to tell me – as some kind of mental self-preservation. Regardless, it is well-known that great suffering and sacrifice leaves you with a dramatically different perspective on life. I neither think nor care about the fact that most people still have the physical faculties I lost. I miss them, obviously, but others having them doesn’t cause me resentment or envy at all; everyone has their own cross to bear.