Mortiis|Vond II

2024-01-31

by Niklas Göransson

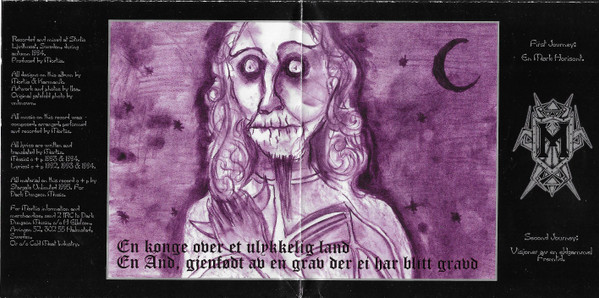

With Født til å herske and Vond’s Selvmord set in stone, Mortiis etched his dark dungeon music legacy into the bedrock of Cold Meat Industry. This alliance birthed timeless classics such as Ånden som gjorde opprør and Keiser av en dimensjon ukjent.

MORTIIS: Mortiis started as a form of escapism. I was heavily into Tolkien, keyboard music, and the mindset and extremities of black metal – all of which shaped the Mortiis project as it continued to evolve and grow. But at the same time, in the mid-90s, I began feeling as if something wasn’t quite right. And that’s when my beautiful depression first made itself known.

How did this manifest?

MORTIIS: I’d have this terrible sense of being out of place – of not fitting in or belonging anywhere. This feeling, I believe, seeped into my music, fuelling my creativity; that’s how I found an outlet for these emotions. I’ve always been good at transforming my mental burdens into artistic creations, and this process is what led to the birth of VOND.

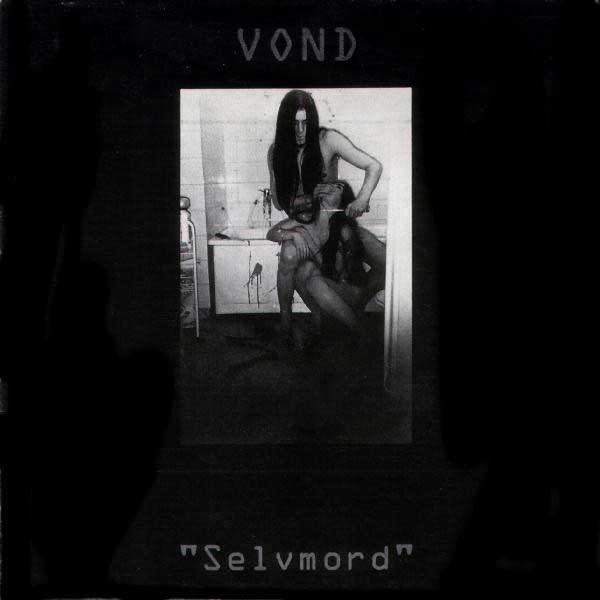

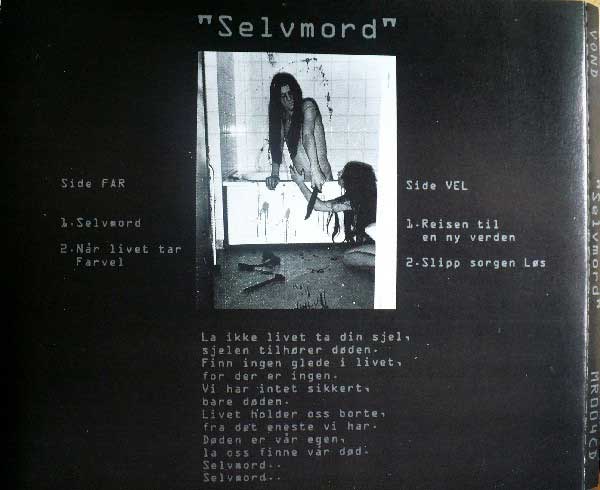

In May 1994, six months after the “Født til å herske” sessions, Mortiis returned to Oslo’s Studio S to record “Selvmord” – the debut album of his side-project, VOND. While Mortiis’ eponymous music explored fantastical and epic themes, VOND ventured into distinctly more sorrowful and melancholic soundscapes.

MORTIIS: In many ways, VOND is rooted deeper in black metal than Mortiis. Especially at the beginning – it was fucking hateful. The later records took a more experimental turn but initially, it was my way of converting the cycle of depression into something creative and constructive. Rather than retreating into isolation and contemplating self-harm, I channelled my emotions into a musical expression.

The poem accompanying the title track, “Selvmord” – which translates from Norwegian to ‘suicide’ – is as well-written as Mortiis’ early EMPEROR lyrics. However, I can’t help but wonder what was going through the mind of the studio engineer during the recording of its spoken word part.

MORTIIS: <laughs> Fortunately, it was the same guy I’d worked with on “Født til å herske” just a few months earlier, so he pretty much knew what I was about. But yeah… can you imagine him listening to me reciting this poetry – basically stating that I’m gonna kill myself any second now? He must’ve thought I was fucking nuts.

Freely translated: ‘Do not let life take your soul, for the soul belongs to death. Find no joy in life, for there is none. We have nothing certain, only death. Life keeps us away from the only thing we have. Death is our own – let us find our death.’

MORTIIS: I can’t remember him saying anything, though. It never occurred to me; I was still eighteen and didn’t give a flying fuck about anyone… walking around in my tight black pants, leather jacket, boots, and bullet belts. ‘Fuck you, world! I don’t care what you think.’ Because, by that point, you’ve graduated from black metal school a couple of years earlier, so the attitude is all there.

“Selvmord” boasts cover art that remains highly effective to this day. I had a VOND shirt as a teenager – in fact, I still have it – with that photo adorning the front and the poem on the back. Not a big hit with the parents, as I recall.

MORTIIS: Yeah, man, that photo is really impactful. My wife and I have been married since 2005; if, for some reason, any VOND stuff resurfaces around here, I must keep that cover hidden because she really fucking hates it. This might have something to do with me being naked with another woman in the bathtub – even though that was ten years before we even met.

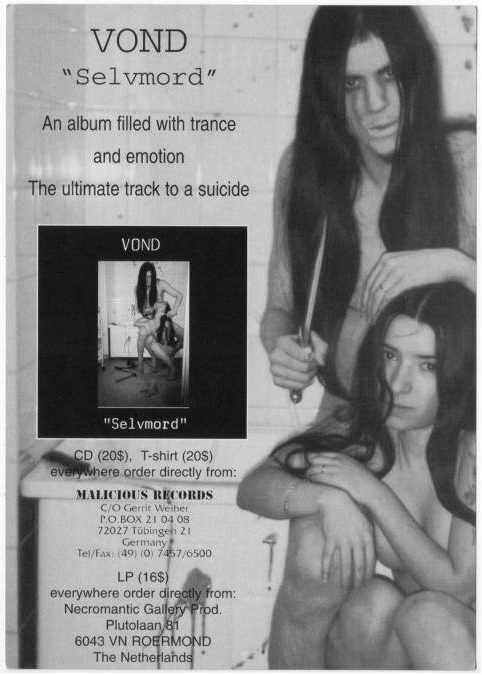

Did it cause any problems with distribution?

MORTIIS: Yes, I believe there were some issues with that CD when Malicious released it. From memory, it got banned in quite a few stores in Germany because… I mean, it’s actually quite artistic but also disturbing. There’s no actual violence depicted, just the suggestion of violence.

What gave you the idea in the first place?

MORTIIS: I wanted to push the boundaries and do something genuinely extreme. I was constantly looking for ways to evolve the black metal aesthetic– not necessarily make it more violently fucked up, but a bit distinct and unexplored, you know? The idea of taking a photo with someone’s head chopped off never appealed to me; it seemed generic and dull, typical of many death metal covers. Instead, I was drawn to the disturbing and suggestive, perhaps inspired by movies like NEKRomantik.

The 1987 film NEKRomantik, directed by Jörg Buttgereit, is notorious for its transgressive content revolving around necrophilia and death. It enjoyed tremendous popularity in the 90s Scandinavian black metal scene.

MORTIIS: Oh yeah – and also Der Todesking and other works of Buttgereit. I felt a much stronger affinity for this style, believing it to be more impactful than showing actual death, mutilation, or gallons of blood. My focus lay on the power of suggestion, which I found more unsettling and frightening than the act itself. In this sense, I was becoming more of an ‘artiste’.

It was precisely such aesthetics that led to Mortiis’ path crossing with the Swedish industrial label Cold Meat Industry.

MORTIIS: You know, it’s weird how things come full circle. Back in the early 90s, I discovered BRIGHTER DEATH NOW in Slayer Mag. There was a photo of this guy sitting on a sofa, wearing a Freddy Krueger-style shirt and makeup that made his eyes look really dark – almost as if they’d been ripped out – with blood pouring from them. And I’m thinking, ‘That’s what we do, but stranger.’ He looked like a normal person who’s been warped by something and was no longer normal.

And that was Roger Karmanik of BRIGHTER DEATH NOW and Cold Meat Industry. At the time of the Slayer interview, BDN had recently released “Great Death” – a pitch-black slab of sonic malice.

MORTIIS: So, I wrote to Roger, only to discover that his band was this really harsh industrial noise. At the time, I had no idea he also ran a label. We started talking and kept in touch over the years. Then, in the late summer of 1994, I sent him some music from “Født til å herske”. He wrote me back and said, ‘Oh my god. Can I release your records?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah’, because I wanted to move on from Malicious.

The German label had still not managed to release the album, nine months after it was recorded.

MORTIIS: Malicious were kind of a mess. Shortly thereafter, I recorded “Ånden som gjorde opprør” in Trånås. That was the first Mortiis album made in Sweden – at a music store with a studio in the back room. I can’t recall the name now, but it was a cool fucking environment. One of the guys working there was the guitarist for SONS OF NEVERLAND.

SONS OF NEVERLAND were a gothic rock band signed to Swedish underground label Primitive Art Records. Their 1995 album, “Soulkeeper”, is a sorely overlooked gem of pure FIELDS OF THE NEPHILIM worship. The studio in question was called Ljudhuset.

MORTIIS: At that point, I had three albums pending. I remember thinking, ‘I’m recording all this music, but it’s not getting released. What the fuck?’ That was frustrating. VOND was supposed to be my side project, yet “Selvmord” hit the shelves before the first Mortiis album – despite having been recorded half a year later.

VOND’s “Selvmord” came out in the late autumn of 1994; the vinyl was produced by Necromantic Gallery Productions, and the CD edition by Malicious Records – who were also supposed to release “Født til å herske” on both formats.

MORTIIS: The delay with “Født til å herske” was mainly due to Malicious fucking around. I guess they didn’t have the funds to press the vinyl and kept delaying it. That’s how it goes when you deal with really small underground labels that are practically run from bedrooms, saving up their allowance to afford printing records. I suppose everyone starts somewhere.

“Født til å herske” was finally released in November 1994 – the first pressing comprised one thousand LPs and one thousand CDs. In retrospect, a severe underestimation.

MORTIIS: Vinyl was on the decline, but I insisted on an LP version. My initial plan was to print at least ten different colours. Even back then, I was keen on the whole ‘One hundred of this colour, one hundred of that.’ People love that concept now, twenty-five years later, but nobody gave a shit at the time. I’d be like, ‘Come on, people – vinyl! What the fuck?’ And everyone went, ‘Oh, but have you seen this new CD thing?’ ‘Yeah, it’s an awful piece of plastic. I hate it.’ But CDs were popular because they sounded more polished, clearer, and so on.

Malicious, however, didn’t go for the colour variety – presumably due to the added costs.

MORTIIS: We ended up with five hundred on black and five hundred on some kind of purple. But yeah, the album did really well. There was never a reissue of the vinyl back then, but more CDs were pressed. Within a year, it might’ve sold five or six thousand copies, which is pretty good for that genre. Especially since Malicious did no fucking promotion whatsoever. It spread the underground way: through flyers, word of mouth, and me sitting there day in and day out, typing out interviews. I also handled a lot of the mail-order stuff myself.

In spring 1995, just before the release of “Ånden som gjorde opprør”, Mortiis was featured on a Cold Meat Industry sampler titled “…And Even Wolves Hid Their Teeth and Tongue Wherever Shelter Was Given”. This compilation brought together veterans like BRIGHTER DEATH NOW, MZ.412, and DEUTSCH NEPAL, as well as more recent Cold Meat acts such as AGHAST, DESIDERII MARGINIS, ARCANA, and ORDO ROSARIUS EQUILIBRIO. It drew considerable interest from both underground metal and the industrial scene.

MORTIIS: Cold Meat seemed to me a far better label than Malicious; they had a much bigger catalogue and operated more professionally. Just before “Ånden…” was released, I asked Roger, ‘What’s your best-selling album so far?’ He goes, ‘IN SLAUGHTER NATIVES, with around two thousand copies.’ And I’m thinking, ‘Fuck. “Født til å herske” has done twice as much. Oh man, I hope this doesn’t mean a drop in sales.’ Obviously, money wasn’t my main motivation, but naturally, you want to be successful. It’s preferable to sell more records than less, if that makes sense.

“Ånden som gjorde opprør” was an instant success – attributable not only to the music but also its extraordinary cover artwork. Mortiis had evolved the mask concept further and entrusted the imagery to Roger Karmanik, a true pioneer in digital booklet art.

MORTIIS: As it turned out, there was no need to worry – Cold Meat treated me well. Roger already had a decent distribution network, but it expanded significantly with Mortiis. It opened many doors, especially into the metal world. And frankly, I think it also positively impacted some of the other artists in terms of exposure.

Mortiis’ importance in the rise of CMI is well established. At the time of this writing, Bardo Methodology is collaborating with Artax Film and Death Disco Productions on a documentary film called Soul in Flames: The Adversarial Fires of Cold Meat Industry.

MORTIIS: Cold Meat had an interesting way of financing records. Roger would give you a certain sum upfront, and that was your money; he’d never ask for it back. Then, any additional studio costs were split between us. This meant you only had to recoup less than half of the actual studio cost, in stark contrast to other labels. Roger was cool like that, with his straightforward approach.

“Keiser av en dimensjon ukjent” – the third Mortiis album in less than a year – was released in late autumn 1995.

MORTIIS: I don’t remember exactly, but I think “Ånden…” and “Keiser…” probably sold around the same amount. I wouldn’t be surprised if they each did at least 15,000 copies. That’s pretty good for a small label like Cold Meat. The first time I received royalties was a complete surprise! I mean, ‘What, I’m getting paid?’ Because, up until then, I was accustomed to selling some shirts and demos and occasionally receiving a couple of dollars in the mail.

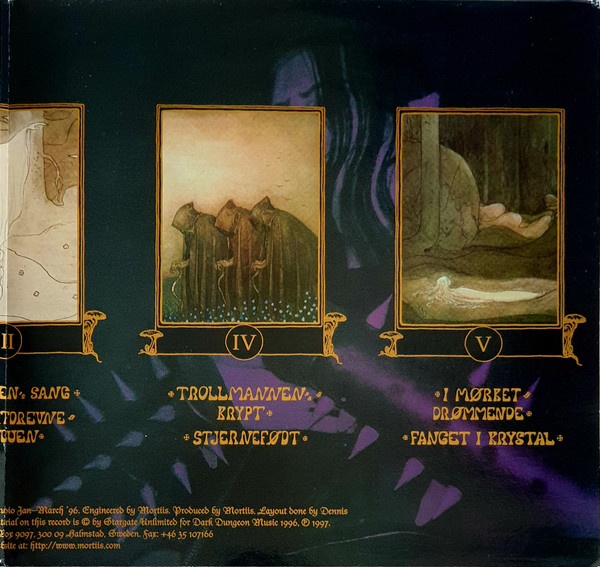

The cover and booklet of “Keiser av en dimensjon ukjent” featured more stunning visuals – not only photos but also the paintings of Swedish artist John Bauer.

MORTIIS: Oh, yeah, I stole all of his artwork. I discovered Bauer in a thrift shop; you know, those Red Cross stores that there are a lot of in Sweden. I doubt you’ll find many John Bauer paintings hanging there nowadays – but these were framed and looked really cool, essentially like enlarged LP covers.

John Bauer was a renowned Swedish artist best known for his work in the early 20th century. He gained fame primarily for his illustrations in the annual fairytale book Bland tomtar och troll, depicting a mythical, enchanted world filled with trolls, gnomes, and other folkloric creatures. Bauer’s style is characterised by dreamlike, ethereal forest landscapes and his distinctive depiction of trolls.

MORTIIS: I’m thinking, ‘Wow, these are fucking atmospheric! Awesome.’ There were three or four of them hanging on the wall, and they cost about three euros each. I didn’t know who Bauer was, but I looked him up and was able to obtain a couple of books. “Crypt of the Wizard” also has John Bauer on it; that record is a compilation of five twelve-inches released separately, all of which had his artwork on the cover.

“Crypt of the Wizard” was released by Mortiis’ own label, Dark Dungeon Music. Worth keeping in mind here is how the music was composed and arranged. Three highly successful albums and five EPs into his career, Mortiis still relied on the same formula he’d used since the demo.

MORTIIS: It’s still baffling to me. Sitting at my keyboard, I’d come up with song ideas – what might be termed base riffs – and then start imagining layers that could enhance them. I had no means of recording snippets and overlaying them with something else, which is typically how you determine if it’s going to blend harmoniously or devolve into atonal fucking bullshit. Playing these melodies to myself, I’d listen and think, ‘These should mesh well’, and just hoped for the best.

So, Mortiis never knew for sure what the music would sound like until he recorded it. Again, these albums sold in the tens of thousands, but the composer himself heard his songs for the first time in the studio.

MORTIIS: I must’ve had a knack for this because it usually worked out. I still can’t play properly, though. I mean, I’m not able to read notes and so on. If I knew how to do that, I could’ve gone all Beethoven. You know, like when an A is supposed to harmonise with another A, or whatever. I had no clue, and honestly, I still find it utterly dull. But surprisingly, most of the time, my brain was on point.

After coming up with a new part, Mortiis would memorise the melody and then add it, colour-coded, into the chaos vortex of scribbled notes that served as his working sheets.

MORTIIS: I would label the first riff, let’s say the bass melody, as blue. Whatever overlaid it was red, and if I came up with something on top of that, it was green. I didn’t layer too much, as that would lead to… issues. Sometimes there’d be a percussion element, marked in green or purple. Typically, I’d use just three or four different colours. And then, in brackets, I’d include some details about how the sound was configured.

Mortiis noted specifics such as the attack and release – meaning, how quickly the sound would start and cease – along with other dynamic characteristics. Clearly, it was a very basic yet effective way to shape the music’s texture and feel.

MORTIIS: So, I dabbled in it , but that was the extent of my programming skills. Nevertheless, I kept writing it all down, and I used the recording method that I mentioned in conjunction with “Født til å herske” – piecing together all these four or five-minute passages, which gradually faded into something else. And that’s how the song would just keep going and floating around till it ended.

log in to keep reading

The second half of this article is reserved for subscribers of the Bardo Methodology online archive. To keep reading, sign up or log in below.