Leviathan I

2024-04-10

by Niklas Göransson

In the first instalment of a three-part series, American musician and tattoo artist Jef Whitehead – also known as Wrest from Leviathan and Lurker of Chalice – looks back on his tumultuous formative years.

JEF WHITEHEAD: The first time I played drums was at my grandparents’ house; they kept a kit up in the rafters. It had a snare and a kick drum, perhaps one tom, and a single cymbal but no hi-hat. Anytime my mom and I went out and there was live music, I’d always ask the drummer if I could fool around with his set. Every so often, someone would let me.

The story of Jef Whitehead begins in July 1969 at Stanton Hospital in California. After six years in Huntington Beach, he moved with his mother to San Jose where they lived until relocating to Santa Cruz in 1981.

JEF: It wasn’t until junior high, when I joined some band-thing they had going, that I started drumming seriously. We performed the music to a school play of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. I probably overplayed because it was a rare chance for me to even touch a drum set.

At thirteen , Jef obtained an acoustic guitar. Unlike drumming, he could now practise an instrument at home.

JEF: The first song I learned was “Hungry Wolf” by X, and then I just kinda went from there. I figured out some stretchy chords from watching music videos with THE POLICE. Their guitarist, Andy Summers… I don’t know what the proper term is, but it’s like he played two power chords at once.

Rather than sticking to conventional chords, Andy Summers would combine notes that are typically far apart to create a fuller and more complex sound.

JEF: I’ve picked up lots of stuff from observing other guitarists. For example, I taught myself barre chords by watching MTV. Barre chords allowed me to use all six strings; you burrow the index finger and then move it upwards, right? You keep playing the E but up the neck.

This technique allows the guitarist to play a wide variety of chords by moving the same finger shape up and down the neck.

JEF: Then I started learning some BLACK SABBATH songs, but they mostly used power chords. Everything from that point on has been by ear, followed by trial and error. The first band I played in was HOME BREW; we opened for MINUTEMEN once, which was mind-numbing to me as a high-school kid.

California punk band MINUTEMEN formed in 1980 and continued until their guitarist and vocalist, D Boon, died in a car crash five years later. They are posthumously regarded as a pioneering act in post-hardcore and alternative rock.

JEF: I went to see a horror film called The Hunger, and it opened with this terrifyingly skinny man and a guitar sound full of echoes and pick scrapes. That was back when you could stay in the theatre and see the movie again. I re-watched the beginning and, lo and behold, discovered BAUHAUS.

BAUHAUS, with their innovative blend of post-punk, experimental, and sinister ethereal sounds, emerged from the UK in the late 1970s. They can be seen performing in a nightclub during the opening scene of The Hunger.

JEF: Furthermore, SIOUXSIE AND THE BANSHEES were extremely important to me. I was also really into the CHRISTIAN DEATH type of… I wouldn’t really say goth, because that term has a much broader scope and even covers dance music. I’m talking about the eerie sounds that originally came from punk, but now there are metal bands like TRIBULATION and NEW SKELETAL FACES in the same vein. I guess it’s called deathrock?

Deathrock evolved from the early 1980s punk scene as a darker, moodier offshoot characterised by atmospheric guitar work, haunting vocals, and transgressive lyrical themes.

JEF: So yeah, I’ve always liked the creepy and more morose stuff. JOY DIVISION are a huge, huge deal to me. Somebody said that punk rock is ‘Fuck you!’ whereas JOY DIVISION are ‘We’re fucked.’ <laughs> ‘Sad bastard music’ is what some of my friends call it.

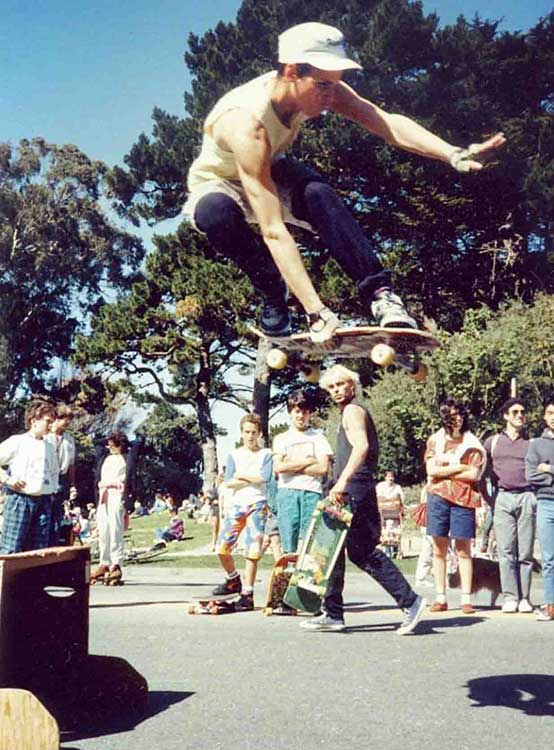

Besides learning how to play guitar, the young Jef also took up skateboarding. To the dismay of his mother, these newfound hobbies held far greater interest for him than anything happening at school. During the summer break between his freshman and sophomore years, Jef ran away from home to his dad in Oakland.

JEF: I kept causing trouble up there too, which resulted in me becoming a ‘ward of the court’ and being sent to live in group homes. After getting kicked out from a few of them, my social worker asked, ‘Okay Jef, where do you want to be?’ I’m like, ‘I told you, man. I wanna be in San Francisco!’ To me, San Francisco represented freedom; that’s also where a lot of punk rock was happening. So, they sent me to live with Father Gregory.

Jef briefly mentioned this episode in a 2012 documentary series called One Man Metal. Father Gregory was the pastor of St Nicholas Orthodox Church in San Francisco. For decades, until his passing in August 2021, he ran a group home for troubled children.

JEF: Father Gregory had good intentions. We were always going to the movies or out for dinner and things like that; we even went to Yosemite once. Of course, there was a lot of fighting among the boys in the house, and I constantly landed myself in trouble. Stuff like coming home drunk or on acid, being argumentative, not going to school, getting kicked out of class, and so on. Basically, just being an angry kid. You know, I never ratted on the fact that some of the counsellors were getting me stoned.

These were the group home counsellors ‘straight out of San Quentin’?

JEF: I remember that at least three of them were, yeah. And it was just odd; they gave us weed and showed us magazines we probably shouldn’t have been looking at. I got into a fight with one of them… I sort of blacked out, which happened from time to time, and started tearing the room apart. Someone out in the corridor put his ear to the door to listen – just as I threw a chair, legs first, right through it. Honestly, it was quite cinematic, but I could’ve killed the guy.

Following his eviction from Father Gregory’s, Jef briefly stayed at a group home in Hayward before being transferred to Oakland.

JEF: The last place had staff who’d actually gone to school for this kind of work and knew how to deal with kids. I remember a woman there named Penny – she was very nice to me. She’d buy me dye if I wanted to make my hair look stupid and was a bit more nurturing. But if you keep causing trouble… enough is enough, and you gotta go. My caseworker told me, ‘That’s it! You’re going to a boys’ farm.’

Having squandered his final chance, Jef was about to be shipped off to a ‘youth guidance centre’ – a facility for juvenile offenders which offered far fewer personal liberties than group homes.

JEF: It was gonna happen the following Monday. The place I lived at organised activities for us every weekend and that Sunday, we went to the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park. I asked, ‘Hey, can I bring my skateboard?’ And they’re like, ‘Sure, whatever.’ As soon as I got out of the car, I just grabbed my board and took off… ‘Hey, come back here!’ I went to my best friend’s house and stayed on his couch.

Is this the friend who was trying to learn every Tony Iommi riff in existence?

JEF: Yeah, Rik. He had a guitar and there was always music playing in that house. Both of us were obsessed with Iommi; we listened to lots of BLACK SABBATH and lots and lots of VENOM. And then I discovered CELTIC FROST. But it wasn’t until much later I found out that they weren’t quite as tongue-in-cheek and gimmicky with the dark stuff as VENOM. Tom G Warrior was pretty serious about all that.

Tom G Warrior’s early work with HELLHAMMER and CELTIC FROST explored various esoteric themes such as archaic rituals, mythology, and the embrace of darkness and death as transformative forces.

JEF: I was unaware of this back then – I just liked the way their music made me feel. And then SLAYER; they’ve been a staple in my life ever since. Of course, there were great thrash metal bands from the Bay Area, like FORBIDDEN and EXODUS. I got to see METALLICA at some small venue back when they all had their real hair.

Did you consider yourself a metalhead?

JEF: Nah, I hung out with everybody. I had a good friend called Dana who was a metalhead. Actually, she still is and now plays in INSECT ARK and SWANS. She wore jeans vests and bullet belts in fucking high school already; she was really immersed in that whole scene. Most underground shows back then were on Broadway – one side of the street was punk, the other side metal.

In the 80s, Broadway in San Francisco’s North Beach served as a hub where punk, metal, glam, and alternative music scenes came together.

JEF: Metallers and punks didn’t get along, mostly because the metalheads were kind of rednecky dirtbags whereas the punks were… a bit different. It wasn’t until “I Against I” (BAD BRAINS) came out that metal fans started going ‘Hey, maybe punk isn’t so stupid?’ I was also into weird shit like BUTTHOLE SURFERS, as well as the punk rock coming out of Texas: M.D.C, THE DICKS, and so forth. But I wasn’t really an anything-head yet; I liked everything.

Besides honing his guitar skills, Jef also ignited a lifelong passion for tattooing.

JEF: Rik’s mom dated a famous tattooer in San Francisco. He’s dead now, but his shop brought over a doctor from Japan who was touring with these human hides. Some Japanese people – I guess Yakuza or whoever, gangsters, and other heavily tattooed people – would bequeath their skins to this guy.

Japanese tattoo tradition involves intricate, large-scale motifs crafted through painstaking methods. Despite strong cultural roots, tattoos in Japan have a certain stigma, particularly due to their association with criminal elements.

JEF: Each hide had been stripped from the arms and entire back of a tattooed corpse; they looked very well-preserved. If you spread one out flat on the ground, it would form a T with a fat middle. I saw them and just went, ‘Wow!’ That experience really stuck with me. My friend Theo Jack made a little prison gun out of a toy slot motor and gave me my first two tattoos – both on my leg.

In 1985, just before turning sixteen, Jef returned to Santa Cruz to live with his mother and her husband. He enrolled in a kind of last-chance school.

JEF: I was supposed to get my GED, but all I did was hang out at a nearby skate park. I went there every day, and that’s when I really honed skateboarding. It wasn’t long before I was sponsored; people were giving me free stuff. Obviously, I still loved music, but skateboarding became my main thing; that was the thirst, everything revolved around it. I ended up getting kicked out again, so I went back to San Francisco in ’86 and moved in with the girl I was dating.

That’s when BEASTIE BOYS’ debut album, “Licensed to Ill”, came out. It made a massive impact on the skateboarding scene, steering many away from punk rock to hip-hop. I wonder if that’s why Jef hates ‘rap metal’ with such passion.

JEF: <laughs> Yeah, many of my friends started getting cornrows, using words like ‘dope’ or ‘fresh’, and caring more about what cars they drove. I remember them cruising around looking for Brass Monkey – a really awful liqueur-type drink that BEASTIE BOYS sing about on that record. Which I always thought was pretty silly, ‘cause it tasted horrible.

Brass Monkey is a premixed cocktail of orange juice, vodka, and dark rum. It gained popularity after BEASTIE BOYS wrote a song by the same name.

JEF: But yeah, many of the kids gravitated towards that. I’ve just never been a fan of hip-hop culture in general. I understand and definitely appreciate rappers who’ve done time in prison and really were gangbanging and then write songs about it. But just like in black and death metal, it’s easy to project things you have no personal connection to.

What I find noteworthy about this timeline is how Jef seems to have stayed largely out of trouble once he’d broken free from both his parents and the system. One would think that an angry and lost seventeen-year-old left to his own devices would promptly find himself either in jail or the morgue.

JEF: You know, I think about that a lot. How San Francisco used to be. Plenty of people I grew up with are now dead or in prison. I’ve never been much of a criminal, though; I just wanted to skateboard, smoke weed, and chase girls. We did a lot of trespassing but never hurt anyone. I mean, we got into street fights and stuff like that but nothing serious. One time, we broke into the old Jim Jones temple <laughs>.

Jim Jones, as in Jonestown?

JEF: Yeah, I’m not kidding – it was right next to a famous San Francisco venue called The Fillmore. Jim Jones had already done his Guyana thing and the building stood unused. My friends and I broke in, tore the plies off the floor, and then put them up against the stage as makeshift ramps.

Jef clearly garnered some recognition in the skateboarding community, as evidenced by his appearance on the cover of a Nintendo game called Skate or Die 2: The Search for Double Trouble.

JEF: I was skating with the professionals in San Francisco every day. For instance, the people who started brands like Real Skateboards and Antihero. The game company called the pros, so we all went down there. I think the guys gave it to me because I never had any money and was always mooching off everyone else. ‘Hey, can I finish the rest of your meal?’ ‘Can you buy me a forty-ounce?’ It’s also a really fake photo.

Do you mean the backdrop?

JEF: No. I don’t skateboard like that; I’m regular-footed. Basically, they had me skate the opposite way just for the shot. That bar was about four feet off the ground, and I had to keep jumping onto it. They kept telling me, ‘Look gnarlier, make your face gnarlier!’ which I found really silly.

Around the same time, Jef was recruited as the drummer of GASM – a band featuring his friend Rik.

JEF: GASM played this kind of 80s funk punk rock. Not like RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS – more in the vein of MINUTEMEN or TAR BABIES, with the old slap bass and crazy guitar and hollering vocals. And then some kid gave me my first drum set. I’d put on RUSH and try to play all of “Cygnus X1” from “A Farewell to Kings”. That’s when I started learning odd time signatures and stuff like that.

Unorthodox time signatures deviate from the conventional 4/4 drumming, breaking measures into uneven beats and creating a rhythm that may feel slightly ‘off’.

JEF: We also started playing live and supported PRIMUS on several occasions. Old PRIMUS, that is – the one called SAUSAGE. I mean, it was super stressful, but I do remember some shows that went quite well. I enjoyed playing live unless we’d been partying too much, which was often the case with those guys.

Rowdy band, then?

JEF: Oh yeah. I was probably shooting myself in the foot regarding skateboarding there, getting loaded every Friday and Saturday. I know for a fact that crystal meth is different where you are. In Scandinavia, it’s more of a paste and a little mellower – whereas over here, it would keep you up for three days straight. That’s actually how I taught myself to play bass: just sitting there, practising until my fingers bled.

Were you primarily into stimulants?

JEF: No, I did a lot of psychedelics all throughout high school. From… shoot, from the time I hit San Francisco at thirteen. Years later, when I was seventeen, we figured out that psilocybin mushrooms grew in Golden Gate Park. This kid I skated with – we called him Hippie Jason – knew how to find them. They looked sort of like bones with bluish streaks. And I distinctly remember that whole summer, we were just constantly on these gross little mushrooms.

You once mentioned ‘losing your mind on LSD’ – was that just hyperbole?

JEF: I did have some meltdowns but was never hospitalised or anything. There were a couple of times when it took me a while to… come back, shall we say? An artist friend – who is kind of a mentor of mine – once told me, ‘It’s okay to lose your mind, as long as it comes back.’ Obviously, he said this to me way later.

Did you get anything positive out of it?

JEF: For sure, I’ve had more beautiful experiences than horrible ones. And it’s not all bad: the paranoia forces you to reflect on your life. I’ve always been one to, in certain situations, attack myself in my head. That’s why I no longer smoke weed; it’s like a psychedelic now. Back in the period we’re talking about, I thought I did everything better stoned. But it’s just too strong these days – when people offer it to me, I tell them, ‘Thanks, but I don’t like thinking that hard.’

Already in their late teens, many of Jef’s friends began battling substance abuse. After two years with GASM, he started having similar issues.

JEF: I hung out with people who took speed all the time, and then I met this kid who was really into MDMA. I still skateboarded, but it started taking a backseat because I’d have to recuperate for a full day or two. At that point, things got a bit messy. I broke up with the girl I lived with, which became a whole thing in itself.

log in to keep reading

The second half of this article is reserved for subscribers of the Bardo Methodology online archive. To keep reading, sign up or log in below.