Nuclear Death III

2025-07-09

by Niklas Göransson

Driven by voices, visions, and a haunted instinct, Nuclear Death gave sound to horrors better left unspoken. Guided not by theory but by possession, Bride of Insect became a transmission from the void.

LORI BRAVO: I’ve always thought it’d be hilarious to hand NUCLEAR DEATH sheets to a proper music theorist. Like, I know those were technically real chords, but I have no idea what the fuck they are. It was never really about the music, though – death, destruction, rape, torture, killing, sadness, rage.

NUCLEAR DEATH emerged as a fusion of German thrash intensity and punk aggression, pushed to extremes by warped riffing and unconventional picking. Drawing equally from DESTRUCTION, DISCHARGE, and horror film scores, Lori Bravo, Phil Hampson, and Joel Whitfield sculpted chaos with deliberate atmosphere – symphonic in texture but feral in delivery.

LORI: Despite having dropped out of school at fifteen, Phil knew how to structure prose. He wanted to be a writer, so I did everything possible to help. I tried submitting his work to Weird Tales; that was the first rejection I can recall. Eventually, he said, ‘Fuck this, I’m done.’ I told him, ‘No, don’t give up. If nobody’s publishing your stories, we’ll put music to them.’

Over their three demos, NUCLEAR DEATH distinguished themselves not only through innovative musicianship but also with uniquely twisted themes. Guitarist Phil Hampson handled most of the lyrics, crafting nightmarish vignettes that feel less like typical death metal and more like deranged fiction – vivid, literate, and psychologically unmoored.

LORI: I said, ‘Maybe that’s what NUCLEAR DEATH is – a soundtrack for your imagination? You write the stories, and we’ll bring them to life.’ It took time for Phil to hone his craft, which is why some of the early material sounds weird. By “Bride of Insect”, things were more dialled in, and the words just came pouring out of him.

In March 1989, three years after forming, NUCLEAR DEATH signed with American label Wild Rags Records and began preparations to record their debut album, “Bride of Insect”.

LORI: Phil would sit in his little corner, zoning out for a while, then hand me essentially finished lyrics. He might say, ‘This verse goes here’, and show me a chord. I’d grab my acoustic guitar, and we’d start arranging. I remember us writing “Stygian Tranquility” exactly like that.

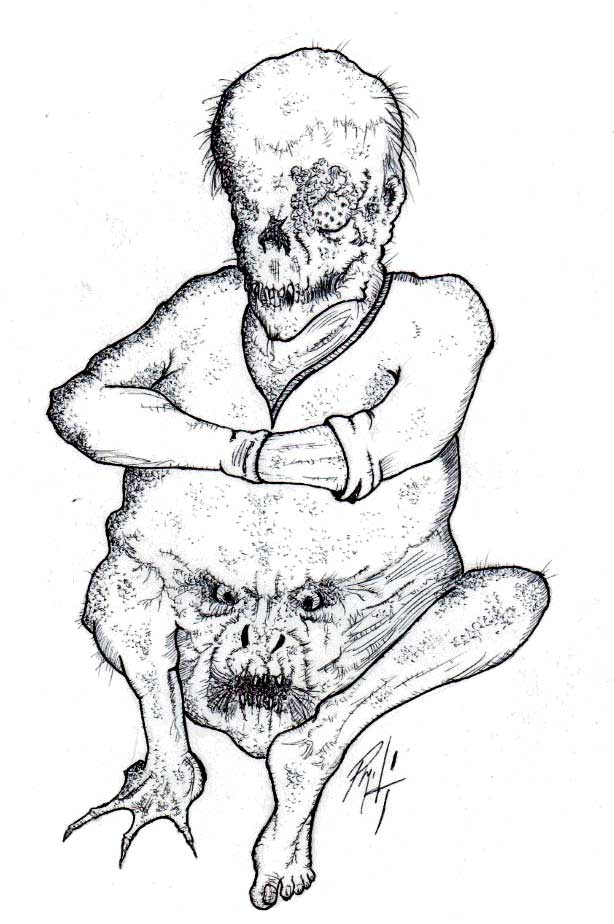

Told from the perspective of a tormented, inhuman narrator, “Stygian Tranquility” merges body horror with surrealist monologue as it drifts through imagery of flesh, filth, and mournful delirium. The protagonist isn’t simply monstrous; it’s conscious, aware, seemingly trapped in its decaying corporeal form. The anguish is existential as much as physical.

LORI: I read the lyrics and thought, ‘What the hell?’ One of the lines went, ‘My eyes sometimes liquify so at times it’s hard to see…’ I was like, ‘Oh my God, that’s horrible.’ Phil said, ‘I think it’s an alien’, and then drew a picture of what he meant. ‘Okay – Lori, you’re this terrible thing, performing these unspeakable acts.’

Did you need a specific headspace to convey this dialogue?

LORI: No. I’m a great singer – as long as the words are right, I’ll bring them to life. It’s theatre, acting. You step into that mind. The protagonist is out there, fucking the roadkill, and I become that. <sings> ‘I crawl upon a dead dog, lying on the edge of a pool of blood / I watch as flies encircle the carcass, and the dog… we make love!’

Listening closely, it sometimes feels like Joel’s drumming enhances the theatricality by syncing with Lori’s narrative – such as the lines she quoted from “Stygian Tranquility”, where there’s a dramatic tom roll beneath the phrase ‘…we make love.’

LORI: Yep. By that point, Joel understood what to do without being told. I’ve always preferred jazz musicians; they have an entirely different sense of nuance than rock drummers and tend to approach the kit with more texture and feel. Their playing actually breathes.

Did Joel take part in the song arrangements?

LORI: Yeah, he’d sometimes offer valuable suggestions. I remember on “Place of Skulls”, Joel proposed a change that really worked. Despite not being a vocalist, he could sing back what he had in mind. We’d just play whatever he sang – since none of us knew music theory, it was all intuitive.

In a 2020 interview with Coffin Nail Productions, Phil said he knew the material was right if he could hear voices in the music – as in the song literally spoke to him.

LORI: Mm, Phil would sometimes mention hearing my voice inside the music. Other times, he claimed to sense spirits – which I absolutely believe. Phil’s a very haunted person, so yes, I think he really did experience that. We always knew a song was truly great when it felt like… possession is probably the best way to describe it, especially in the early days.

Do you mean possession in a supernatural sense?

LORI: Yes, especially as I began figuring out how my voice worked within the music. I felt totally possessed – not by autonomous spirits or entities, but by the song itself. Honestly, with our core line-up at its peak, it often seemed like we were conjuring something. Spooky as hell yet incredibly creative.

Similarly, in the same Coffin Nail interview, Joel said he used to pull drum parts from static on TV or radio.

LORI: Yeah, he’d get really stoned – though usually not around us – crank up the volume and listen to static. I remember Joel talking about hearing things in it. Other times, he’d catch a riff from the way a passing truck backfired. He’d store that sound in his mind; maybe use it later, maybe not.

“Bride of Insect” was immortalised between September 3 to 4, 1989, at Vintage Recorders in Phoenix, Arizona. This time, Joe ‘Crow’ Correo – who’d handled the first demo three years earlier – returned as engineer.

Structural abrasiveness aside, the playing itself is tight; tracks like “The Beloved Whore Celebration” and “The Misshapen Horror” reveal calculated control beneath the turmoil. They must have rehearsed the shit out of this material.

LORI: Not at all. Phil and I practised together constantly – just the two of us, in our bedroom, running through everything. Then we’d head to the rehearsal space, fire up the amps, and work through the songs on our own. Eventually, Joel would wander in for the last two hours.

Joel didn’t like rehearsing?

LORI: No. Sometimes he showed, other times not. NUCLEAR DEATH never rehearsed our material the way people seem to think. Phil and I were tight; that’s probably where the locked-in sound comes from. Joel was a good enough drummer to just listen, feel it, and drift in and out of the music.

The aforementioned “Stygian Tranquility” is a prime example of Joel’s celebrated use of unorthodox time signatures – something that became central to NUCLEAR DEATH’s sound.

LORI: You must have misunderstood. See, Phil tended to rush or play over everyone, just all over the place. Joel recognised this early; he had a strong internal clock and could keep time. Same with me – whenever Phil veered off, I’d adapt around the bass and hold it together.

So, you’re saying that much of the percussion innovation really came from Phil’s erratic riffing?

LORI: Exactly. He’d speed up and lose tempo; not always, but often enough that we had to play around it, which is where the chaotic feel comes from. Honestly, though – it worked. Our music wouldn’t have been what it was without this unpredictability. We were still learning.

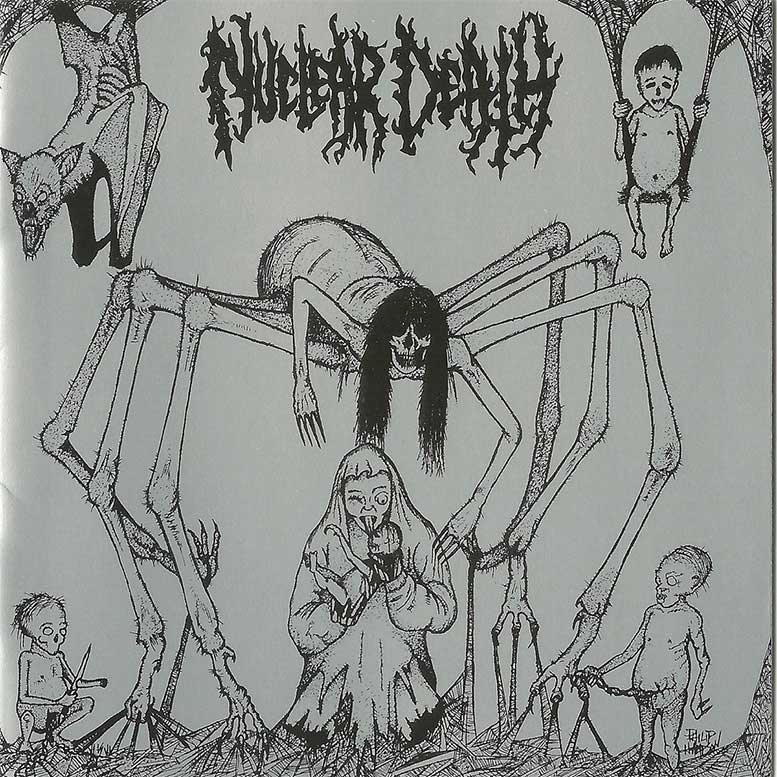

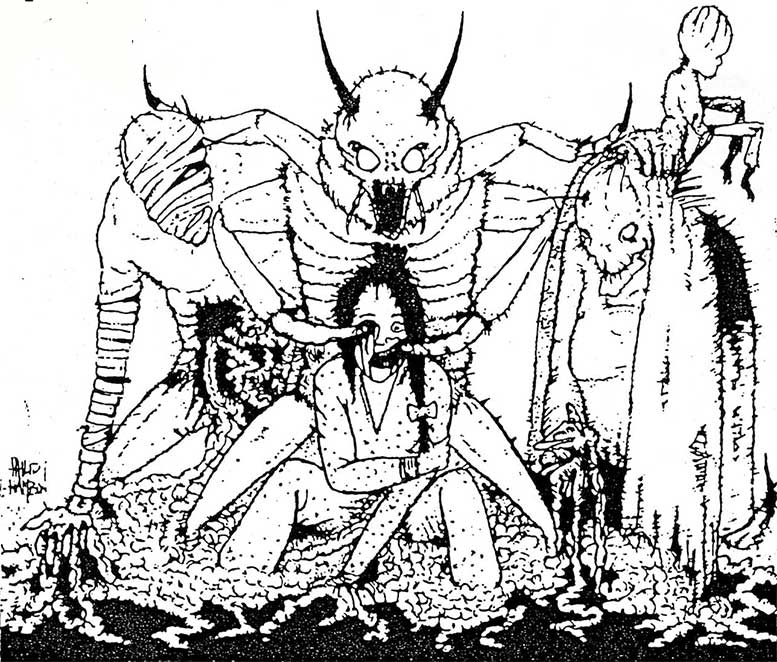

When “Bride of Insect” finally saw vinyl release the following year, it arrived with the perfect cover – the grotesque imagery feels like a direct visual translation of the music.

LORI: Phil was really in his element, which is why the “Bride of Insect” artwork turned out so strong. I’d already designed the logo years earlier, back in 1983, but refined the iron thorns for the album cover. And it’s readable – unlike these idiots now, doing logos you can’t even decipher.

The cassette edition, also courtesy of Wild Rags Records, featured a different cover illustration.

LORI: When drawing her, Phil used a photo of me. That’s what’s on the cassette insert – me, in pyjamas, Christmas morning. He always made it feel sexual with those weird insect hands. He’d say, <creepy voice> ‘You’re my Bride of Insect.’

Although officially issued by Wild Rags, the label’s involvement seemed more akin to wholesaling than genuine financial backing. Lori’s parents funded the recording, even taking out a loan to support their daughter’s ambitions, and the post-release promotion was virtually non-existent.

LORI: Right? Richard C was more of a distributor than anything else. He pretended otherwise, but that’s a fucking fact; Wild Rags didn’t finance shit. And nothing he actually did matched our contract.

During the early 1990s, Lori worked for several carpet cleaning companies in Arizona, often holding managerial roles.

LORI: I started at Freedom Carpet Clean, which shut down because the owners were total cokeheads. After that, Diamond Carpet Cleaning popped up; I got hired there, but they also turned out to be drug addicts. Then I moved to another one – similar deal, different name, same result. It was like a revolving door of dysfunction, but somehow, I always found ways to keep working.

These jobs were crucial for sustaining NUCLEAR DEATH’s operations, funding tape trading and DIY promotion to fanzines. Once appointed manager, Lori could hire her bandmates.

LORI: Phil worked there for a while, Joel too. As did my brother and his best friend, plus our roadies, Andre and Joe. We got paid every Tuesday, and the whole crew pooled money for a giant bag of weed. Because of that job, we managed to rent a van and go on tour.

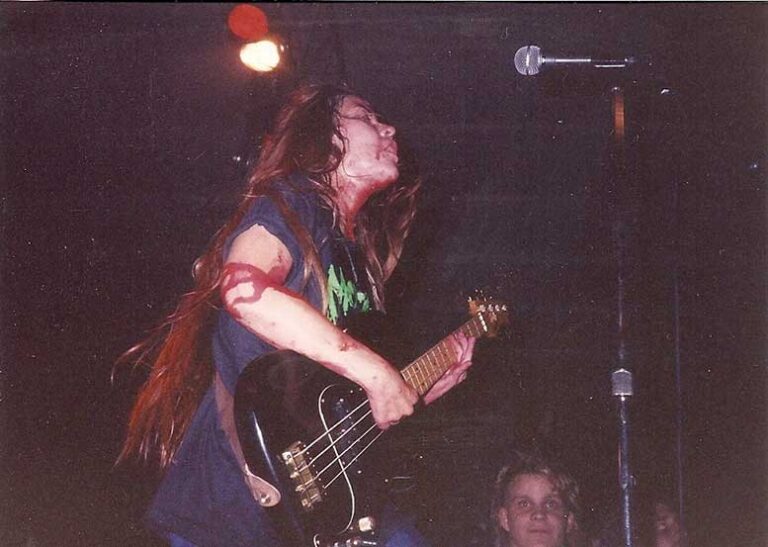

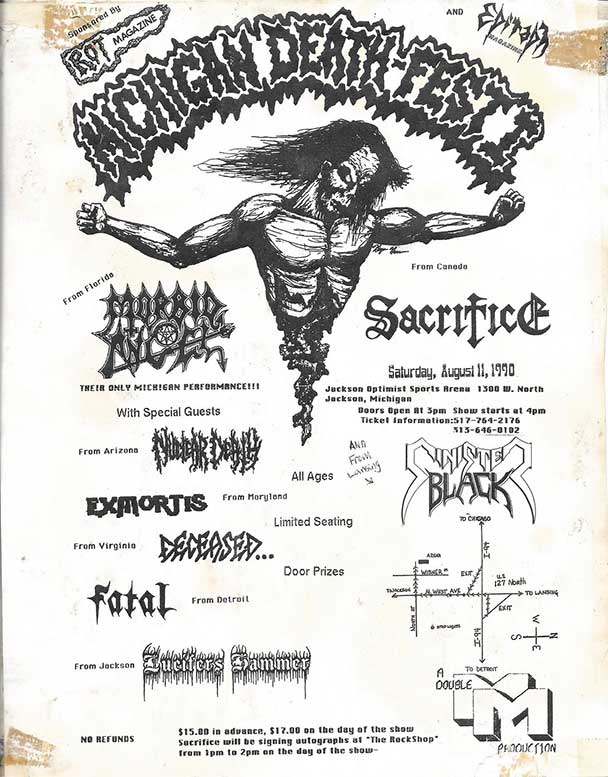

In August 1990, to promote “Bride of Insect”, NUCLEAR DEATH embarked on their first proper mini-tour.

LORI: Driving to Texas from Phoenix, we got pulled over by state troopers looking for drug dealers. I didn’t know shit about cartels or whatever back then. These fuckers confiscated our weed and made us pour out the beer – but upon realising that we were just weirdos going to play music, they let us go.

NUCLEAR DEATH performed three shows – El Paso, Houston, and McAllen – all captured on footage later released as the Unalive in Texas VHS.

LORI: Houston’s where I realised I needed glasses because I couldn’t read the fucking setlist. El Paso was more of a warehouse-type space. The tour concluded in McAllen, and that’s when I discovered how much love and support my Hispanic brothers and sisters have for artists. Coolest people ever.

How did the internal band dynamics hold up while touring?

LORI: I mean… Joel pulled his usual nonsense. We were supposed to leave, and suddenly he’d gone missing. Turns out some girl had taken him to see the Gulf of Mexico. As always, we had to sit around waiting while he was off screwing around. Typical Joel bullshit.

Looking back, would you have liked to do more touring?

LORI: Oh, absolutely. If it were up to me, I’d tour constantly. I love being on the road – I love driving, even though I didn’t back then. I’ve always enjoyed motion, never staying in one place too long. So yeah, I would’ve loved to do more touring… and I still might.

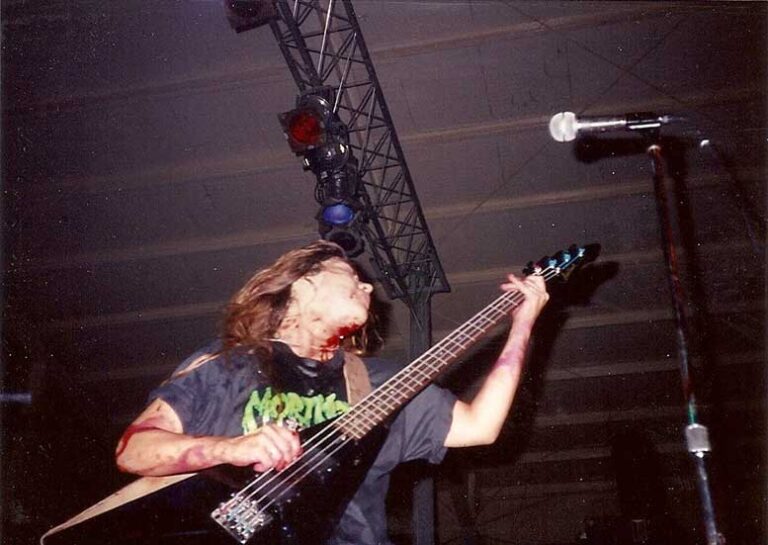

Just a week after the Texas shows, NUCLEAR DEATH played Michigan Deathfest.

LORI: A fan helped organise it… though I can’t even remember the man’s name now, which I feel terrible about. He reached out and said, ‘Hey, NUCLEAR DEATH ought to play Michigan Deathfest. I’ll hook you up.’ An old penpal of mine, Stan Bowman, let us crash at his place in Joplin, Missouri, on the way there.

log in to keep reading

The second half of this article is reserved for subscribers of the Bardo Methodology online archive. To keep reading, sign up or log in below.