Nuclear Death VII

2025-07-29

by Niklas Göransson

Fuelled by insomnia, chemical devotion, and artistic obsession, the new Nuclear Death duo retreated from the world and spawned The Planet Cachexial – a soundscape of isolation made flesh.

LORI BRAVO: “All Creatures…” was a stepping stone of sorts – the bridge that let me cut ties with Phil, prove I could handle NUCLEAR DEATH on my own, and then move forward. And you know what happened next: “The Planet Cachexial” took us exactly where we needed to go.

Following the November 1992 self-release of “All Creatures Great and Eaten”, NUCLEAR DEATH had no label, few touring prospects, and seemingly fading interest from the local scene.

LORI: There was no internet, no fan mail, no indication that anyone cared anymore. We financed everything ourselves, so touring meant paying out of pocket – and by then, I didn’t even know who to call. I had completely lost touch with anyone you’d normally hit up for live shows.

Around this time, the pair vacated their house on Steve’s parents’ property and moved into an apartment in Phoenix, across from a library. While there wasn’t much musical activity, they were anything but idle.

LORI: We were constantly off our heads on meth. And with me already being someone who never sleeps, all I did was create – non-stop. Painting, drawing, making jewellery… I gave away tonnes of handmade indigenous-style pieces. Baked my own clay from caliche in the desert. Painted everything. It never let up.

After a frantic, meth-fuelled surge of creativity with little direction, Lori discovered the work of American science fiction author Philip K. Dick.

Best known for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and A Scanner Darkly, Dick was a visionary whose fractured narratives explored identity, paranoia, and the nature of reality. A fellow amphetamine enthusiast, Dick reportedly wrote entire novels in manic bursts, surviving on little more than speed and canned food.

LORI: My brother recommended Philip K. Dick, and that’s what got me rolling on the idea of writing my own sci-fi novel. I finished the full story and illustrated the eighteen-page Slumberblood book in under a week. That’s insane. Sometimes I look at it and can’t believe how lucky I was.

I’m inclined to suggest that the meth played a role.

LORI: Sure, the drugs helped open things up, but the creativity was already in me – I’d known that for a long time. I wrote the story for fun, just to see where it would go. Then I thought, ‘Maybe I can sell this?’ I had no idea how to publish a book, but Steve said, ‘We should make a soundtrack for it.’ And I went, ‘Yeah, let’s do that.’

What kind of music had you envisioned at this point?

LORI: I wanted to push the idea of NUCLEAR DEATH as a narrative score even further. I’ve always loved bands with a storytelling approach – TRIUMPH, IRON MAIDEN, that sort of thing. “2112” by RUSH and PINK FLOYD’s “The Wall” are two of my most important albums. I told Steve, ‘Let’s take the ending of “All Creatures…” and build an entire album around it.’ Bam! High five, hit the meth, and I’d just sit down and write.

Lori and Steve fell into a highly focused creative rhythm – cutting themselves off from outside distractions, living in isolation, immersed in writing and art.

LORI: I read something – maybe Patti Smith, maybe Robert Mapplethorpe – that convinced me we should disconnect from society and just be artists. So, we cut out TV and radio completely, and it worked beautifully. We lived this tight, boxed-in life in our apartment; that pressure bled directly into “The Planet Cachexial”.

Did you still listen to records during that time, or were you avoiding other people’s music altogether?

LORI: No, we were constantly playing CDs. WEATHER REPORT, and various sorts of jazz. Then I’d pull out Hank Williams, Hank Jr., Robert Johnson – it became all about studying music, art, and artists. That library across the street had Miles Davis albums we’d never heard before, like “Dark Magus”.

Originally released in 1977, “Dark Magus” captures Miles Davis live at Carnegie Hall. Dense and hypnotic, it’s a double album built around extended improvisations and polyrhythmic intensity.

LORI: Steve and I were speeding out of our minds, barely sleeping, just absorbing everything; that headspace seeped into the music. I wanted to take it somewhere expansive and open-ended – like Miles Davis’ “Agharta” or “Bitches Brew”. “The Planet Cachexial” has structure, sure, but the songs breathe in a way they never could with Phil around.

I’m not very familiar with many of your influences, so I can’t really trace them in the music. Was Miles Davis the most important one?

LORI: Absolutely. Check out his fusion period. If you go on YouTube and watch him live for two hours – and really listen – you’ll hear “The Planet Cachexial” in there. I don’t know how you couldn’t. That’s where it lives: in the idea, the energy. It’s avant-garde.

Lori and Steve wrote most of the material in 1993 and early ‘94, all the while sticking to their artistic bubble, entirely disconnected from contemporary music and popular culture.

LORI: We missed the entire grunge wave – NIRVANA, HOLE, all of it. Steve’s shady buddies from school would sometimes drop by. A few were alright, but it still meant outside stuff creeping in – on his end. I had nothing. No social life, no distractions. Steve was my best and only friend.

Was that by preference?

LORI: Absolutely. That’s how I got things written – by having everyone leave me the hell alone so I could do what needed to be done. “The Planet Cachexial” was both of us, sure, but I wrote most of the material. Those songs are mine. Steve arranged and performed them, but the melodies, the ideas, the whole vision – it all came from me.

Was it all-new material?

LORI: No, “Ve’at” was originally called “Crystal Hollows”. I wrote it in high school for a guitar class. The teacher wanted us to learn some stupid four-chord song, but I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cooler if I just made my own?’ So I did. Instead of going, ‘My God, this girl composed her own tune!’ that miserable old prick failed me. Anyway, what you hear in “Ve’at” is exactly, note-for-note, what I came up with at fifteen.

“The Planet Cachexial” is structured as a conceptual sound narrative – complete with characters, arcs, and environmental sound design. It portrays a surreal alien world shaped by dreams and Lori’s fascination with otherworldly horror.

The guitars favour clean, dissonant layers over the distortion-heavy style of earlier NUCLEAR DEATH. The band’s signature picking technique remains, but it now promotes tension rather than aggression. Lori’s vocals often consist of wordless shrieks, howls, and pained cries – more texture than lyrical delivery. Though entirely her own, the approach brings to mind Diamanda Galás.

LORI: I knew of her – Metalion (Slayer Mag) sent me a dub of “Wild Women with Steak-Knives” back in the tape-trading days. As great as she is, there was no influence. This is all me; these are the characters I become. The only time I’m not one of them is when I narrate “Into Zyrèlyà”.

The aforementioned “Ve’at” serves as an intro to “Into Zyrèlyà”, the only track one might describe as a metal song. It also stands out for featuring actual singing with discernible lyrics.

LORI: That narration – when I say, ‘Into the void, he was sucked…’ – is me telling a story as a person. It’s the only instance where I’m not inhabiting a creature. Everywhere else, I become them: the Zyrèlyàns, the Overseer, the Elder Body, Slumberblood, Mother Chaos, the Wiengd with scissors for wings. I embody each one.

Once the songs began taking shape, did you and Steve actually jam them together – with a guitar amp and a drum kit?

LORI: Man, I have no recollection of how we actually rehearsed… I think it was at Steve’s parents’ house. Mostly, we just sat around the apartment smoking meth, with Steve tapping rhythms on the floor while I played an acoustic or plugged my guitar into a little practice amp.

As creatively productive as this sounds, I’m curious about the health implications. One rarely hears uplifting stories about long-term methamphetamine use.

LORI: I’ve always been the responsible kind of drug addict. I made sure to eat, sleep, and drink water. I didn’t lose my teeth or anything gnarly like that. But yeah, my skin broke out – acne all over, constant itching. Your body’s in overdrive. I started getting lines under my eyes; I’d stare at myself in the mirror, going, ‘Jesus, I look sixty!’ So, you hydrate. Whatever.

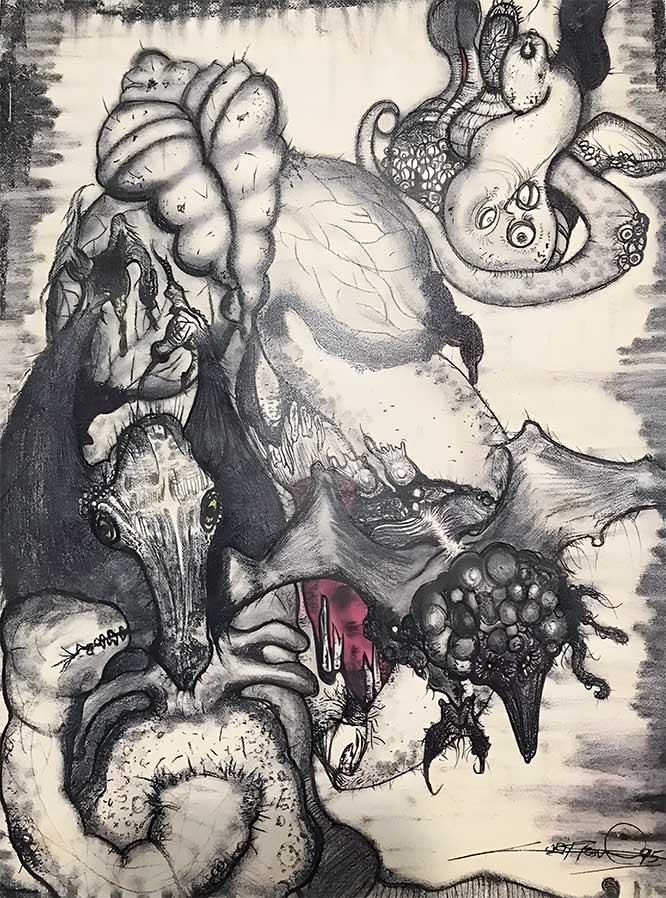

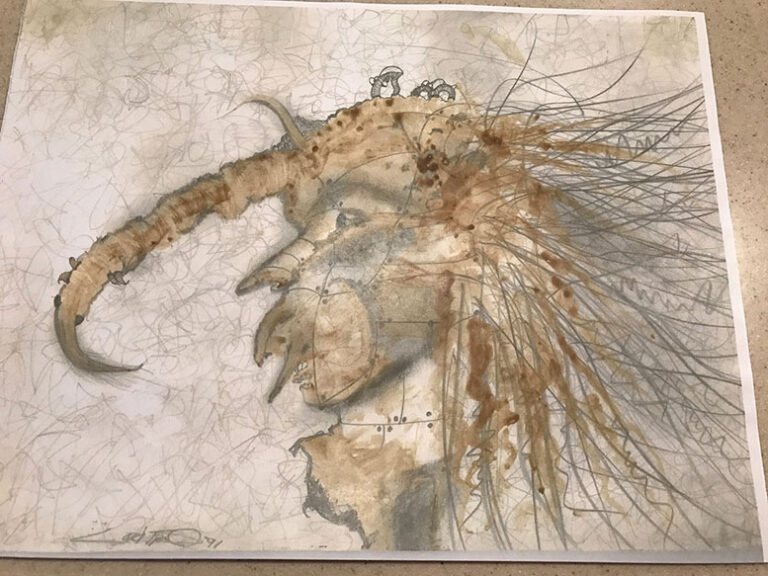

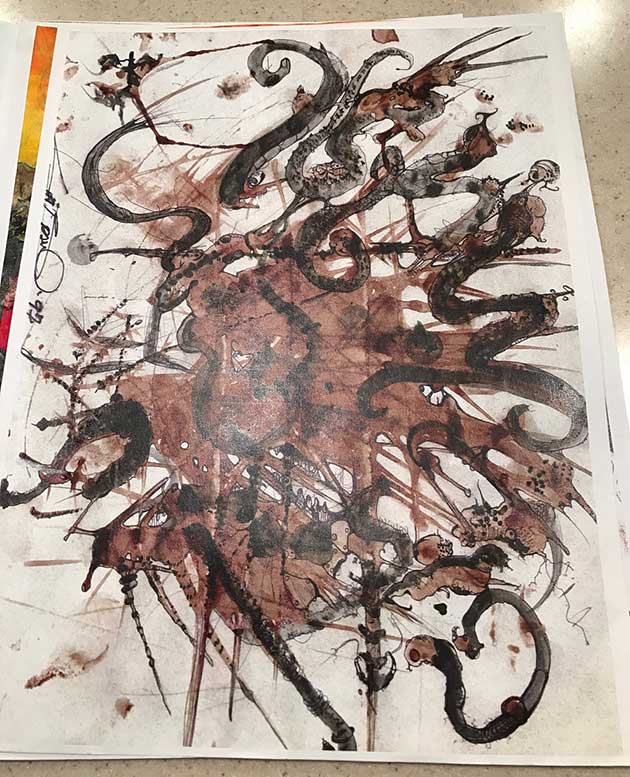

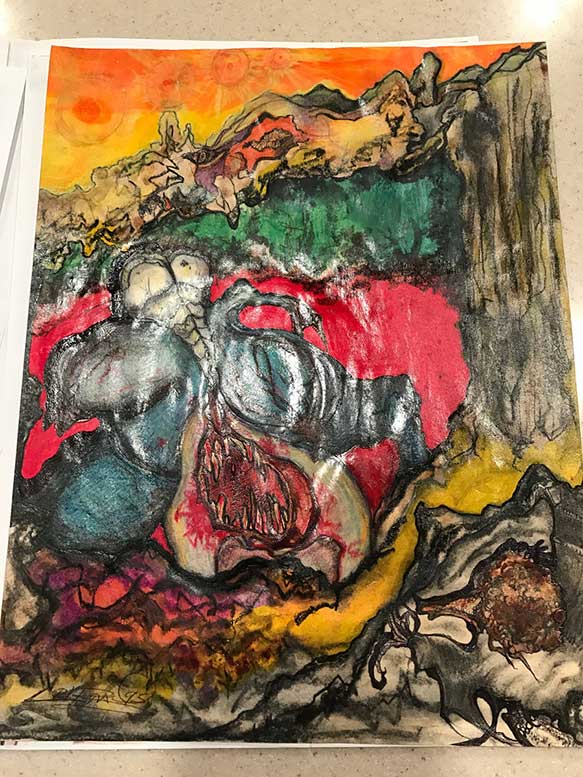

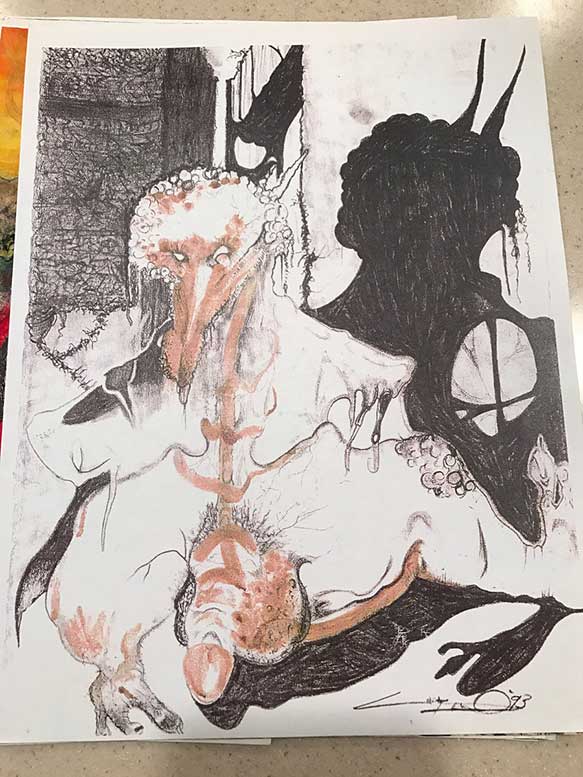

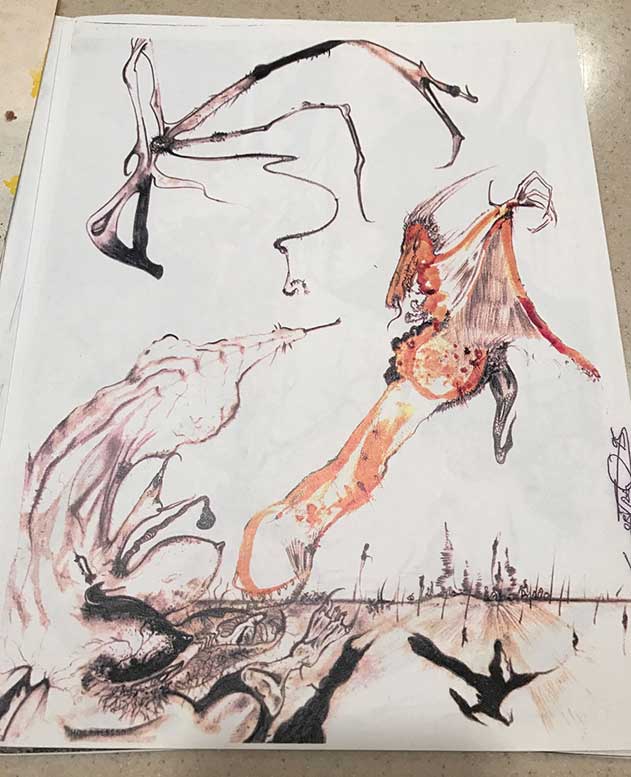

While Steve focused on refining musical arrangements, Lori created the artwork. After studying Salvador Dalí, she produced a series of illustrations for her novel.

LORI: I wanted to translate Dalí’s feel without colour. Back in grade school, I was in what they called challenge art. My teacher introduced me to charcoal, still one of my favourite mediums. I love the stark contrast of black and white. There’s some colour – a hint of red pencil in the Overseer’s eyes, for example – but most of the brown you see is my own blood.

Besides blood and charcoal, some of the finer details were drawn with a ballpoint pen.

LORI: Characters like Grimalkin and the Wiengd – those I did in colour. I thought it’d be amusing to use crayons in what I considered fine art, so I went for it. Dalí inspired my thinking about shadows and light, but I was also hugely influenced by British illustrator Gerald Scarfe.

Best known for his grotesque, exaggerated style, Scarfe’s surreal animations famously brought the psychological themes in PINK FLOYD’s “The Wall” to life.

LORI: He’s one of my favourites. And Heavy Metal: The Movie. As you probably know, my next ambition was to make Slumberblood into a film. Of course, this could never have happened back then. Today? If I met the right person, maybe.

Once all the music had been composed and arranged, the next challenge was figuring out how to capture it properly with limited resources.

LORI: I had everything mapped out in my head already; the whole symphony was there. I just needed Steve to tune into it. I knew we wouldn’t be able to afford an ensemble, or anything close. Nowadays, you can simply press a button to simulate an entire orchestra – but not back then. No computers, no shortcuts, just whatever we could make happen ourselves.

Neither of them had any credit, which made renting instruments impossible, so they turned to Lori’s parents. Her father agreed to co-sign for anything she needed.

LORI: I suggested, ‘Let’s start with one instrument at a time.’ Trumpet was first. Steve also bought bongo drums, congas… and when my folks went abroad, I told them, ‘If you see anything strange, get it. If you can blow into it, Steve will figure it out. If it’s got strings, I’ll use it.’ They came back with a haul: a didgeridoo, a Kenyan finger piano, African flutes, and various Nigerian instruments.

Did you end up using any of them?

LORI: Most, I’d say. We even built instruments ourselves. I’m looking at one right now – kind of a bass, crafted from the inner frame of a cactus. It’s topped with vertebrae, maybe cow bones, strung with wires. You play it like a bow: ‘Ding, ding, ding, ding.’ Still sits in the corner of my bedroom.

Throughout 1994 and 1995, Lori and Steve made a pre-production demo of “The Planet Cachexial” with their own eight-track setup. Once everything fell into place, they entered Chaton Recordings in Scottsdale, Arizona.

LORI: I remember playing the solo for “Into Zyrèlyà,” and something kept sounding off. I was like, ‘God, why does this feel wrong?’ Our amazing engineer, Demitri Sahnas, goes, ‘Let me take out the hi-hat.’ Boom! Problem solved. Everything else went like clockwork. Totally smooth.

log in to keep reading

The second half of this article is reserved for subscribers of the Bardo Methodology online archive. To keep reading, sign up or log in below.