Nuclear War Now! Productions I

2025-12-23

by Niklas Göransson

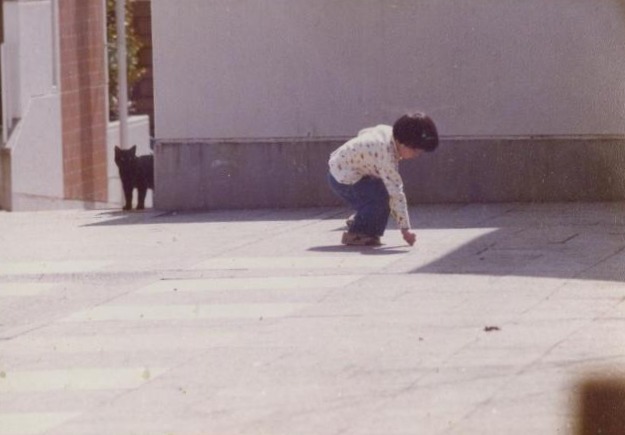

Before Nuclear War Now! took form, its foundation was laid in displacement. Born into a culture of cohesion, Yosuke Konishi came of age within disorder – shaped by subcultures rather than classrooms, guided more through instinct than belonging.

YOSUKE KONISHI: I have some recollections from my childhood in Japan – mostly how free everything felt. Kids more or less roamed on their own because society was extremely safe and, for the most part, made up entirely of Japanese people. Back then, it really did function as an ethnostate.

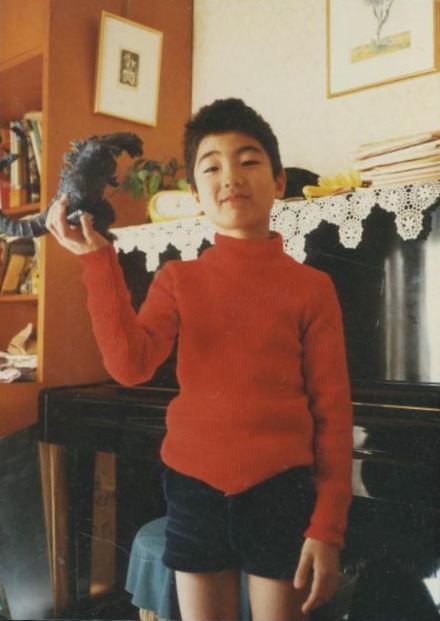

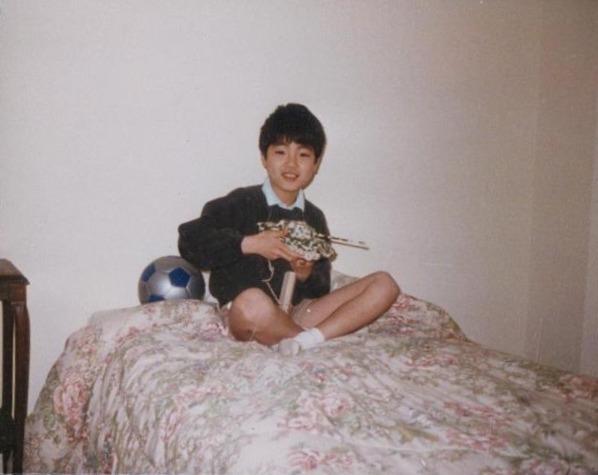

Born in 1976, Yosuke Konishi grew up in a modest apartment in Tokyo’s Tama district, living with his mother, two sisters, and a stepfather.

YOSUKE: My parents divorced early, and I have no memory of it; I must’ve been a baby. Instead, I grew up with a workaholic stepfather who barely registered in day-to-day life. I remember the small apartment the five of us shared – two bedrooms and a tatami room.

A tatami room is a traditional Japanese living space lined with woven straw mats, typically used for sleeping, receiving guests, or everyday family life.

YOSUKE: There was another space connected to the kitchen that my mom, who was an art teacher, turned into a studio. An enormous lithograph press – about the size of a Volkswagen Beetle – sat right in the middle, with a chemical bath next to it. So, we’d be eating breakfast while inhaling paint fumes <laughs>.

Considering your current workspace, would it be fair to say that this sensory environment left a lasting imprint?

YOSUKE: Absolutely. We’ll get into it later, but I live at the N.W.N! compound these days – and with the vinyl factory running, I’m breathing melted PVC all day long. You could definitely say there’s a straight line from my childhood to where I am now.

Yosuke’s stepfather – a news correspondent for Mainichi Shimbun, one of Japan’s oldest and most prominent daily papers – was largely absent. His mother, by contrast, belonged to an artist collective and often brought her children along to exhibitions and social gatherings.

YOSUKE: I remember this beach party she took us to; a group of lithograph artists were hanging out, and one of them thought it’d be hilarious to tickle me until I pissed my pants. Then I had to take the train home like that – an hour-long ride because of the crazy Tokyo traffic. I sat there, miserable the entire way.

YOSUKE: I was definitely a curious kid and spent a lot of time in nature. Japan feels incredibly urban, but only on the flat stretches; walk far enough and you hit forest. Most of the country isn’t even inhabited – it’s too mountainous and volcanic, so people cluster along the coasts. Even suburban Tokyo has plenty of wooded pockets.

While the Tama district lies west of Tokyo’s urban core, it long retained a semi-rural character, with wooded hills, river valleys, shrine forests, and farmland stretching toward the foothills of the Kantō mountains.

YOSUKE: My friends and I would wander into the woods and eventually end up in a huge rice field. I remember wading into the flooded paddies, trying to catch whatever lived in there. That’s what Japanese boys did – we went after beetles, snakes, anything crawling through the dirt or hiding in the water.

That sounds decidedly less safe than the urban environment.

YOSUKE: One day, we came across a bee’s nest. I must’ve disturbed it somehow because I got swarmed and stung all over. When my mom heard what happened, she told the other kids to pee on me – supposedly, ammonia reduces the venom’s effect, though I have no idea if that’s actually true.

As it turns out, human urine contains only trace amounts of ammonia – nowhere near the concentration required to neutralise or meaningfully reduce insect venom.

YOSUKE: Afterwards, she gave us some change to buy popsicles, and I can still remember the exact brand I chose. Given how deeply that whole experience is burned into my memory, it must’ve been an excruciating ordeal – first getting stung everywhere and then pissed on.

At age eight, Yosuke’s world expanded overnight when his stepfather’s work as a newspaper correspondent brought the family across the Pacific to the United States.

YOSUKE: I don’t remember the exact moment he told us, but I distinctly recall the whole family being against the move – especially my oldest sister, who was already in high school. She ended up staying behind to finish her last few years, then joining us later.

All Swedes of my generation grew up with American films, television, and music – but you had none of that, right?

YOSUKE: No. Japan was the world’s leading tech exporter, so we had our own cultural output. Almost everything was produced internally, including entertainment. I don’t know if you’re familiar with anime – Japanese animation – but Hokuto no Ken, or Fist of the North Star, shaped me just as much as metal did.

Based on a popular comic book, Hokuto no Ken became one of the defining anime of the 1980s: a post-apocalyptic martial-arts saga whose hyper-violent style and larger-than-life heroes moulded an entire generation of Japanese youth.

YOSUKE: I had no awareness of US comics until I arrived here and realised how big that whole world is. As far as I remember, the only Hollywood movie I’d seen before moving over was Gremlins; my stepfather thought exposing me to American pop culture might be a good idea.

For the first few months, the family lived in an apartment in Ballston, Virginia – an Arlington suburb of dense residential blocks, office buildings, and a metro line into downtown Washington DC. While the modest lodgings echoed their Tokyo home, the society outside proved a sharp contrast to Japan’s monoculture.

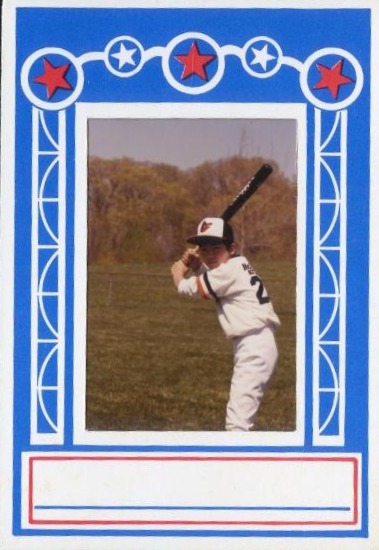

YOSUKE: Not long after we arrived, my parents made me join Little League Baseball. I played on a team with a girl who was actually pretty good, and another kid who was black. I criticised her in front of him, and he turned around and said, ‘Don’t talk shit – you’re a ching-chong’, or something to that extent. Instant wake-up call.

To what?

YOSUKE: Like, ‘Okay, I’m not in a homogeneous society anymore. If you run your mouth, there are consequences.’ I also remember the total chaos of navigating the DC metro. I’ll never forget the smell in those trains – a mix of burning rubber and piss. And the homelessness was on another level.

Were there none of the ‘unhoused’ in Tokyo?

YOSUKE: Sure – but in Japan, being homeless is often a conscious withdrawal from society, or the result of financial hardship alone. Most are perfectly normal to talk to; you don’t get the ones screaming at the sky, because those people end up institutionalised. In the US, they just don’t do that for some reason.

After six months in Ballston, the family bought a house in Falls Church – a small city in Northern Virginia, quieter and more suburban than Arlington, with good schools and easy access to the Mainichi Shimbun office at the National Press Building in Washington DC.

YOSUKE: After moving to Falls Church, I’d often visit the public library on Route 7. My sister and I went there constantly, trying to absorb American culture. One time, we borrowed a DEVO VHS with all their music videos. What grabbed me was how they existed in the mainstream yet still felt completely outsider.

Musically, DEVO were rooted in jagged new wave and synth-driven art rock. By 1985, they’d already released a string of influential albums and were entering their electronic phase – a period marked by “Shout”, which became the first physical music media Yosuke ever bought.

YOSUKE: “Shout” definitely set off the avalanche of record collecting that ended up taking over my life. The way you consume music as a kid, when you’ve got endless time, is completely different. I’d spend hours just listening, studying everything – the artwork, every nuance in the songs.

Yosuke has credited DEVO’s fusion of art, satire, and sound for shaping his view of music as a total aesthetic experience – where everything from artwork to attitude has to serve the same vision. Anyone familiar with N.W.N! will recognise those principles.

YOSUKE: The music was strange, but not as weird as the imagery. I don’t know if you’ve seen DEVO’s videos, but they’re pretty fucked up – not disturbing in a dark way, just wildly different from anything you’d expect in American culture at that moment.

The following year, an intern at Mainichi Shimbun who tutored Yosuke and his sister in English introduced them to the soundtrack of Repo Man – a 1984 cult film best known for its now-iconic collection of early American punk bands.

YOSUKE: That intern – a college student – was also into indie rock, which my sister liked much more than I did. But the Repo Man soundtrack blew my mind: it had BLACK FLAG, CIRCLE JERKS… and I’m pretty sure SUICIDAL TENDENCIES were on there too.

How did that listening experience compare to DEVO?

YOSUKE: I’d say the rawness of punk rock helped me truly understand the role aggression plays in music. The Repo Man soundtrack was basically my gateway to punk, metal, and the underground as a whole; it’s the true origin of N.W.N! and a precursor to everything that came after.

Considering first the move to the US, and then this intern – has it ever occurred to you how profoundly that Japanese newspaper shaped your path in life?

YOSUKE: No, I never thought about it that way. There’s actually another interesting Mainichi Shimbun connection: my stepfather subscribed to every major English-language paper, so stacks of them were always lying around. I found the logo I still use today in a Washington Times column about gun control; I cut out the illustration and tucked it away.

YOSUKE: I really enjoyed how easy school felt in America compared to back home. I was ahead in almost every subject and ended up placed in a maths class with older kids. And I wasn’t even a good student in Japan – because even then, I cared more about the arts than academia.

Is that a testament to the quality of Japan’s education system, or a lack thereof in the US equivalent?

YOSUKE: I don’t know; maybe it’s American culture in general? There are obviously plenty of smart people here – but if you’re curious about something and want to learn, you’ll probably have to figure it out on your own. This society doesn’t really value intelligence or flexing your brain cells.

Yosuke’s mother was an avid jazz enthusiast and would take him to live performances around DC. I know very little about this genre – but as I understand it, jazz improvisation often hinges on structure hidden inside chaos. A balance not unlike extreme metal.

YOSUKE: Those shows opened my mind to sounds that felt formless but could still be interpreted as music. My tolerance for a perceived lack of song structure probably goes back to all the jazz I heard at home. I’m not a musician, though, so my listening experience differs from someone who plays.

Yosuke did actually have a brief stint as a jazz musician in middle school. I must say, envisioning the twelve-year-old N.W.N! proprietor struggling to play the saxophone is outrageously amusing to me.

YOSUKE: My mom pushed me into it, probably because she’d always wanted to be a musician herself. That’s the kind of thing parents do. I played for maybe a year – from seventh to eighth grade – before pleading with her to let me quit. By then, I was getting way more into skateboarding.

By the late 1980s, skateboarding had become a firmly embedded part of American adolescence. An antithesis to formal instruction, it thrived as an unsupervised street-level culture where progression came through observation, repetition, and peer influence.

YOSUKE: My parents bought me a piece-of-crap Toys R Us board for Christmas. The following year, at summer camp… it’s embarrassing to admit, but I stole money from another kid and bought a proper, professional skateboard <laughs>. I really regret it now, but that’s how everything started.

After immersing himself further in the skateboarding scene, Yosuke’s musical tastes shifted toward thrash metal, crust punk, and hardcore.

YOSUKE: The whole culture felt more suburban back then, and the soundtrack around it was metal or punk. METALLICA had their own skateboard, and companies like Skull Skates and Zorlac were rooted in that kind of aesthetic. It didn’t turn urban and hip-hop-driven until much later – at least not in the DC area.

YOSUKE: The older kids at the skate spot would blast MINOR THREAT, D.R.I. and SLAYER – that’s how I got exposed to it. Their cars were plastered with band stickers, so you’d memorise a logo, then head to a record store and buy whatever looked familiar. You couldn’t sample anything back then – sometimes you struck gold, sometimes it was a complete disaster.

Can you recall any examples of the latter?

YOSUKE: After hearing some kid play “Screaming for Change” by UNIFORM CHOICE – great album, proper hardcore – I screwed up and bought “Staring into the Sun”, from when they’d turned into this awful indie-rock band. Of course, I still listened to it; when you’ve only got ten tapes, you don’t have the luxury of ignoring something that’s already paid for.

In Bardo Methodology #5, Yosuke mentioned an early observation of the contrast between Japan’s disciplined martial aesthetic and the banality of American visual culture. Punk and hardcore are, in many ways, an inverse of the former tradition – which makes their pull on him especially interesting.

YOSUKE: I probably internalised the American value system pretty quickly, which is why that stripped-down, teenage-angst sound of MINOR THREAT, BAD BRAINS and CIRCLE JERKS – all those archetypal bands – hit so hard. Scenes popped up elsewhere too, but the core of it came from here and strongly reflected US culture.

YOSUKE: I started seeing myself as more American with each passing year. Still, I was often reminded of my ‘otherness’ because very few Japanese families lived in Northern Virginia back then. Given its proximity to Washington DC, there was some urban influence – but it wasn’t nearly as multicultural as today.

By 1989, five years after the move, Yosuke still attended Japanese school on Saturdays. I imagine these classes were somewhat more orderly than regular high school.

YOSUKE: As I assimilated into US culture, the Japanese educational environment began feeling almost alien to me. The behaviour, the discipline, the structure – all of it seemed totally disconnected from the American chaos I’d grown to enjoy. Eventually, I begged my parents to stop sending me.

For a Japanese kid growing up in the US, those years also meant encountering World War II through an American classroom lens. I can only imagine how strange, perhaps even conflicting, it must’ve been to learn about the 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

YOSUKE: The narrative is slowly changing now, but my history teacher back then– and most Americans, really – always framed the nukes as an inevitable necessity. I don’t remember feeling insulted by it, though. Most Japanese people have internalised the war as something that happened and needs to be moved past.

Was it ever discussed at home?

YOSUKE: No, my family avoided the topic altogether. The average Japanese person doesn’t revere the Imperial period – it’s more or less swept under the rug as a shameful chapter, mainly because of how badly the country was defeated. Maybe some of the older generation feel differently, because Japan got cucked over time, but I don’t know enough about that mentality.

YOSUKE: Moving from punk into the early grindcore era wasn’t a huge leap. I loved CORROSION OF CONFORMITY’s “Eye for an Eye”, which is pretty chaotic, so I already had a foundation in noisy music. Bands like NAPALM DEATH were punks before they became metalheads.

At thirteen, Yosuke’s Peruvian friend Francisco introduced him to emerging British grindcore acts such as CARCASS and NAPALM DEATH.

YOSUKE: Francisco’s family were Peruvian diplomats. His older brother – maybe sixteen or seventeen – played a big role too. Both of them were miles ahead of your average punk or metal kid in terms of knowledge, digging much deeper into the subterranean stuff. I gravitated toward those guys for information.

log in to keep reading

The second half of this article is reserved for subscribers of the Bardo Methodology online archive. To keep reading, sign up or log in below.